by Amy Fagin | Jun 15, 2021

Introduction

Arts-based teaching strategies in genocide studies are rapidly reaching a globally influential threshold. A growing body of pioneering courses and inspiring arts encounters have contributed to arts and aesthetics based public interfaces and pedagogical initiatives around the world. Global research in arts-based-learning demonstrates that these constructs are enriching and shifting direction in genocide studies and prevention. Still, arts-based education is ascribed only a secondary place rather than an integral one in genocide studies and prevention. This essay makes the argument that arts and culture initiatives, their conception, creation, curation, dissemination, and engagement can play foundational roles in orchestrating responsible memory, transitional justice processes, and sustainable, transformative genocide prevention. Consequently, the need to engage in structural curriculum development across the interface between arts education and genocide studies is essential. Full examination of academic inquiry, professional training, interdepartmental and inter-institutional collaborations in the study of genocide and its prevention can facilitate the emergence of a “grammar” for arts education that negotiates cultural history and collective violence.

Frameworks for Adopting Arts-Based Pedagogy in Genocide Studies and Prevention

Precisely how does arts and cultural expression and education elucidate the relationship between culture and conflict? What parameters in arts education and expression need to be re-imagined and what will dispel outdated institutional approaches, ethics, and practices to those that activate collective, creative, and constructive dialogue? What policy and educational paradigms in arts expression and education have proven to reduce the risk of conflict and / or mitigate escalation of conflict? What are the correlations between artistic and cultural engagements and their corresponding schools of education and how can they be designed to initiate and influence peace and reconciliation processes?

I work with two “frameworks” for considering the parameters for developing arts based educational curriculum as an essential component of genocide studies and prevention. First, I consider the U.N Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes Tools for Prevention. This document examines and addresses the “risk assessment factors” in understanding how mass atrocities escalate. In this analysis mass violence is understood as a process, a set of risk factors and a continuum. Within this continuum, I argue that arts production, curation, appreciation, dissemination, and education is an essential tool for mitigating risk of mass violence at every stage of escalation. As the Framework for Analysis “risk factors” indicate, as systematic attacks escalate against civilian populations, opportunities for the arts to address violence decreases. Along with this deterioration, avenues to facilitate creative dialogue which builds trust, empathy, and social justice processes, proportionally decrease. One can conclude that the role of arts and culture’s influence can mitigate escalation of violent conflict, build awareness outside the conflict area, and foster local, regional, national, and international debate and dialogue that encompasses multiple points of view.

It is important to note that contemporary armed conflict and mass atrocity crimes have undergone a shift from earlier generations of historic, inter-state warfare to new patterns of violence which increasingly are attributable to contracted identity-based conflict. (Naidu-Silverman, 2015). The emergence of such patterns of violence can be identified in the Framework of Analysis by risk factors such as weakened or poor governance, increasing instability and triggering factors such as autocratic regime-change or natural disasters. Definable patterns of intergroup tensions can emerge from unaddressed past human rights violations or socio/economic, identity-based patterns of discrimination. According to the Framework for Analysis a lack of “mitigating factors” such as robust independent judiciaries, civil society, open-media, and international collaboration can deteriorate social cohesion to the point where escalation of violence becomes predictably imminent. What is not fully developed within this framework are those “mitigating factors” where arts-based initiatives can foster prevention. The framework only briefly outlines efforts that include “accountable national institutions, protecting human rights (and) managing diversity constructively” (Nations, 2014).

The second article that I use for articulating the specific conditions where arts and culture initiatives can serve as tools for prevention are from the essay “The Contribution of Art and Culture in Peace and Reconciliation Processes in Asia”, written by Ereshnee Naidu-Silverman, Senior Director for the Global Transitional Justice Initiative. In this article Naidu-Silverman builds on the Framework for Analysis by thoroughly identifying the parameters where arts and culture can mitigate conflict and violence, within different types of social constructs and during different phases of conflict as such:

“State Repression and Authoritarianism: During periods of state repression and authoritarianism, art and cultural activities can serve different purposes. For example, events such as music festivals, documentary films, and art exhibitions can raise awareness about the oppression.

- Serves as an early warning of conflict

- Supports resistance

- Raises awareness

- Promotes rebellion

In-conflict: While conflict contexts may prove dangerous for artists, when accessible, safe, local performing art events, and traditional ritual ceremony (or art expression) , for example, could serve the following goals:

- Relativizes the conflict

- Shows sympathy and concern for those affected

- Serves as a coping mechanism

- Renews hope.

Post-conflict: In the aftermath of conflict, there is a range of recovery and reconstruction needs. Activities such as commemorative ceremonies, memorialization initiatives, performing art productions, film and visual art could serve broader rehabilitation and reconciliation needs:

- Healing and therapy

- Creates spaces for dialogue and engagement

- Facilitates empathy

- Promotes new identity formation

- Recognizes victims

- Fosters cross-cultural fluency

- Builds tolerance

- Rebuilds trust.” (Naidu-Silverman, 2015, 10)

She outlines the importance of the relationship between constructive dialogue and safe, creative spaces and practices that allow for reflection and peacebuilding between people with differing “ideas, opinions and assumptions to come together to listen to each other without making judgments or particular conclusions.” Encounters within these constructs, she elucidates, can “provide opportunities for former opponents to create joint imaginary solutions to social issues”. (Naidu-Silverman 2015, 10) Essential reconciliation measures such as empathy, cultural sensitivity, advocacy and education as well as evaluation for best practices are all employed in arts arenas where mitigating intolerance, discrimination and identity precursors to violence can be addressed structurally, constructively and creatively.

uilding from these two frameworks, it is clear that connecting the public with difficult histories through arts and cultural expression demands that educational institutions employ innovative pedagogical tools which address this intersection. I reiterate Naidu-Silverman’s points to provide a foundational set of markers to establish these paradigms for curriculum development for aesthetic genres, whether creating, curating, studying, researching, or providing a visitor experience of the “culture-conflict” relationship.

Interdisciplinary curriculum that does not limit or prescribe the function of art can support the learning of conflict history and memory as organic, innovative, and creative prevention strategies. In order to facilitate the breadth of contributions to reconciliation through arts and culture that Naidu-Silverman outlines, educational facilities need to broaden the study of current trends to include the full spectrum of arts genres and modalities engaged in addressing “difficult knowledge”. New paradigms in arts pedagogy which encourage academic and community debate and dialogue toward social cohesion, creative and inclusive community as agents for positive change can be universally incorporated.

In considering new concepts for pedagogy, expanding educational disciplinary horizons to include the study of comparative aesthetics, art criticism and current artistic knowledge are also critical new paradigms. Some key general questions to consider: What is the dynamic between pedagogy of artistic production, expression, and analysis within a situational / identity construct of social aesthetics related to collective trauma? How is artistic expression influencing the aesthetics of collective / public memory, memorialization, and the national and international debates over collective remembrance of traumatic events? What are the thematic / pedagogical links between academic learning, public experience of aesthetic works, heritage curation, collective memory, transitional justice, and atrocity prevention? And what are best practices to consider for implementing a curriculum that fosters integration between academic learning and public arenas of cultural knowledge?

I introduce for discussion here nine forms of aesthetic expression and pedagogical approaches / questions considering new paradigms for instruction. Each of these sections re-imagine concepts which explore public cultural expression and spaces, aesthetic considerations in public memory, cross cultural understanding, community building, and atrocity prevention as exemplars.

Visual Art

Visual art and memory are integrally linked. When information comes into our memory system from sensory input it needs to be encoded so that we can store and retrieve information. The “image” is one of three forms of encoding that enable the mind to store and process information. (Acoustic or sound, and semantic or meaning are the other two encoding forms we use to create, store and retrieve a memory.) What can we learn, and how can we teach about the creative process of visual art in reckoning an “artist’s truth” and memory construct of a massive atrocity? What is the “language of images” and how do we interpret acculturated “constructions” in works of art as a curated truth and memory of collective violence? How does the aesthetic experience with a visual art object broaden predetermined ideas into a deeper understanding and help engage the viewer into new and diverse ways of thinking? The intersection of visual arts education and conflict prevention offers new dimensions in creating, viewing, and exploring visual art as a constructive interface between reality and imagination, truth and memory, prevention and art practice.

Photography

Photography has played an indelible role in documentation, interpretation, witness, litigation, collective memory, and artistic encounter in the visual survey of genocidal specter since the inception of the art form to the present. All known 20th and 21st century mass atrocities claim a copious if not contentious legacy of dissemination of photographed visual documentation. Discourses on their uses and abuses are the subject of over a century of global evolution in visual vocabulary and adaptation to this singularly unique and critical image based aesthetic form of creative expression. Curriculum development in the intersection between pedagogy in photography, genocide studies and prevention should incorporate early critical works on photography and mass atrocity and contemporary developments. Some key questions to consider are the following: What is the role of photography and the relationship between photograph, photographed, and public perceptions? How are dimensions in digital photographic shifting the entire field of contemporary genocide studies? What new digital methodologies, technologies, practices and ethical dimensions in will support and challenge conventional paradigms and re-imagine new approaches in the interface of photography with genocide studies and prevention?

Music

Intuitively, the experience of creating, listening and contemplating music seems a distant star to the catastrophic trauma of the experience of genocide. Yet, the culture of sound dimensions, and of musical compositions could not be more “attuned” to capturing and expressing what might be the ultimate terror, the bottomless grief, the staged propaganda or the trans-generational legacy of genocide; that echoes in the hearts and minds of all human beings. What are the intersections between music and genocide? Was music available during genocidal massacres? What music was created by survivors, witnesses, or musicians from unrelated creative spheres? How has music been incorporated into understanding the paradox of opposites, transcendent soundscapes redefining the abyss of genocide? How can music literature, theory and practice pioneer pedagogical approaches, reflections and perceptions on the study, practice and performance of music and genocide?

Literature

The international relevancy and impact of vibrant world literature that analyzes an aesthetic conveyance and response to mass violence has never been more timely and potentially globally catalytic. The world of letter arts represents a huge consortium of deeply complex genres that demand artistic reflection and reader appreciation toward awareness and understanding in the creative exploration of the nature and consequences of mass violence. Critical literature that resonates across spatial and temporal limitations, and that harnesses the power to impact national and international dialogues on “finding words in the age of violence” are recommended key pedagogical considerations in developing curriculum.

Film

Narrating genocide through film is one of the most widely distributed forms of acculturated communication on the subject around the globe. Cinematic representational genres, from epic historical depictions, intimate memoirs, drama, comedy, and musicals to innovative mixed-media creations all struggle to contain and convey the mammoth historical overlays and contemporary interpretations of the unfathomable reality and tragic legacies of mass violence. Yet film and its industry undeniably, has popularized genocide awareness more influentially than any other creative medium of expression. What is the confluence of the foundational and current issues in the examination, comparison, and challenges within the field of filmography and genocide scholarship? In what ways does film pedagogy confront the problems of manipulated narrations of collective memory, historiography and the boundaries between filmed narrations and realities in the aftermath of mass violent crime?

Theater and Dance

The transformative / transcendental power of experiencing a theatrical / dance production is a universal phenomenon that spans over 2500 years of human history. Theater as a form of historical representation, of the staging of traumatic, memory has a unique role in the larger purpose of inquiry and conversation about genocide and prevention. Dance as a form of spatial and kinetic movement exploring “creative geopolitics” and “place-responsive choreography” can deepen understanding of the relationship between trauma and the body, historical staging, and contemporary experience. What new methods and questions of performative “re-presentation” of collective historical processes and shared experiences of mass violence through acting and dance performance arts can be envisaged in theater and dance pedagogy?

Museums

Critical theory on museology, critical museum studies, theorizing museum practice, and the study of the evolution of the museum in contemporary public discourses are essential learning spheres to explore prior to addressing the equally important questions as to why global communities are increasingly reckoning with the legacy of mass atrocities and trauma through the creation of memorial museums. The paradigm of the “museum” as an institution where the “museum curator as authority” is decentralizing to “visitor with engagement agency” as part of the visitor experience, world-wide. Memorial museums are often on the front lines of grappling with inclusiveness, cultural persuasion, and best practices with contentious histories. Questions on new paradigms in museum studies, theory and practice that explore the intersections of cultural venues and atrocity crimes, human rights and curatorial considerations include (but are not limited to) the following: How can the museum of conscience today dispel old trends in mono-vocal, authoritative curatorial practices and incorporate self-reflective, performative, and custodial roles? How do these visitor cultural sites build inclusivity in presenting contentious histories? How can dialogue, reconciliation and political transformation be curated where potentially antagonistic viewpoints can co-exist?

On Memorials and Monuments

Memorials and monuments represent a tangible, object-based expression of material culture that mark a physical representation of collective memory. They represent expressions of “public memory” which are shaped by interpretative recollections. Memorials and monuments stand at the center of dialogue, debate, controversy and global, public remembrance of events, ideas and those individuals who are recognized for shaping history or who make claims to public memory. Understanding the scholarship and critical theory on the history and evolution of monuments and memorials is an important orientation to understanding the evolution which structures the plethora of contributions and problems of contemporary memorials and monuments addressing collective trauma, memory, and their contentious counter-memories. The discourse between history, memory and place are crystallized in the monument. From generation-to-generation agendas of the dominant culture often ascribe the cultural context of a public monument or memorial. As cultural norms shift, or political power structures shift, the representational attributes of a monument or memorial can be seen as an anathema or misrepresentation to current collective sentiments. Thorough and integrated critical inquiry on the history and current trends in memorials and monuments can support a global network of remembrance that frames debates through commemoration and conversation.

On Digital Space

The implementation of digital technology into arts / aesthetic expression and experience represents a burgeoning constellation of disciplines which has revolutionized arts production, distribution, curation, and viewer / listener experiences. Combined with digital platforms for testimony, documentation and story based digital learning the impact on the “culture-conflict” interface is nothing short of revolutionary. First and foremost, digital platforms improve access and accessibility to information / objects and performances and the potential for spatially condensed dialogue. Bringing artifacts to light with augmented reality tools greatly enhances the dimensions of learning through layered, immersive, experiential interface. Gaming technology offers constructed immersion experiences with disparate geographical locations, cultures and histories challenging more static conceptions of all aspects of life. A “deterritorialization” and “reterritorialization” (Bisschoff, 2017) of place and space will inevitably re-define cultural horizons.

In the wake of the trauma induced by the pandemic of Covid-19 there has been a catastrophic demise of “in-person” forms of performance and visual arts encounters. In response, innovative platforms, and practices on digital media have broken new ground in mediating these challenges and have ushered in creative responses on the cultural frontline. Re-structuring, re-imagining, and re-building the cultural community through digital spaces and with the integration of digital technology will redefine our relationship to arts expression and experience, overall. Incorporating skills in adaptive learning, metacognition, collaboration, and resilience are critical learning dimensions that need to be addressed in working with digital space, arts expression, and experience. New analytic enquiry in theoretical links between digital media, creativity, methods, and practices are essential new paradigms to consider.

Conclusion

Imagination is the catalyst and defining principle for all art expression. In this essay I have made a case for initiating and implementing arts / aesthetic-based pedagogy as standard curriculum requirements included in all post-secondary genocide studies and prevention programs. Re-imagining curriculum is now an essential aspect of education across the planet in the wake of Covid-19. The arts are no exception and have the added challenges of re-inventing traditional methods of practice and appreciation which require hands-on instruction and audience attendance and participation. As we witness Covid-19 re-structuring and destabilizing the entire globe, the time to re-imagine the role of the arts and arts pedagogy is now. Attempts to polarize, consolidate power, restrict access to goods and services and the rise of serious violations of international human rights and laws have taken hold in many countries. We are experiencing an equivalent rise in risk factors associated with mass atrocity crimes in these same locations. As I mentioned in my opening paragraphs, as risk factors for violence escalate opportunities to address violence through arts and aesthetic expression decrease proportionally. Furthermore, the arts community has experienced a disproportionate decline in the ability to operate, due to the fact that “non-essential” activities have been necessarily curtailed to stave off risk of Covid-19 infection at performances or public access indoor spaces. Re-imagining the role of arts in genocide studies and prevention programs should include broadening its scope to the innovations of digital technology to augment and disseminate arts encounters and educational opportunities. There is no better time than NOW to incorporate the proposals for framing arts education within the rubrics of the U.N Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes Tools for Prevention and Naidu-Silverman’s prevention recommendations within curriculum and across academic disciplines. I have introduced central questions to re-imagine learning constructs for each of the nine main branches of art expression to facilitate incorporating new paradigms for building atrocity prevention standards into course and curriculum design. As challenging as this moment in global affairs is, the opportunity to dispel old parameters and instill new paradigms could not be more advantageous. Re-imagining prevention through education and thinking through art has never been more critical nor more important.

Bibliography

Ahmed & B. Crucifix (eds.). (2018). Comics Memory: Archives and Styles. Palgrave MacMillan.

Bennett, J. (2005). Empathetic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art. Stanford University Press.

Bisschoff, L. (2017). The future is digital: an introduction to African digital arts. Critical African Studies, 9:3. 261-267. Taylor Francis Online.

Crowder-Taraborrelli, T., Wilson, K. (2012). Film and Genocide. University of Wisconsin Press.

Dean, D., Meerzon, Y., Prince, K. (2015). History, Memory, Performance. Palgrave MacMillan.

Gabriel, S. P., Pagan, N. (2018). Literature, Memory, Hegemony: East/West Crossings. Palgrave MacMillan.

Goodall, J., Lee, C. (2015). Trauma and Public Memory. Palgrave MacMillan.

Keightley, E., Pickering, M. (2015). Photography, Music and Memory: Pieces of the Past in Everyday Life. Palgrave MacMillan.

Klimczyk, W., Swierzowska, A. (eds.). (2018). Music and Genocide. Peter Lang Publishers.

Lehrer, E., Milton, C., Patterson, M.E. (2011). Curating Difficult Knowledge: Violent Pasts in Public Places. Palgrave MacMillan.

Milton, C. (2014). Art from a Fractured Past: Memory and Truth-Telling in Post Shining Path Peru. Duke University Press.

Naidu-Silverman, E. (2015). The Contribution of Art and Culture in Peace and Reconciliation Processes in Asia. Danish Centre for Culture and Development.

Sodaro, A. (2018). Exhibiting Atrocity: Memorial Museums and the Politics of Past Violence. Rutgers University Press.

Torchin, L. (2012). Creating the Witness: Documenting Genocide on Film, Video and the Internet. University of Minnesota Press.

United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect. (2014). Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes: A Tool for Prevention.

Waller, J. (2016). Confronting Evil: Engaging our Responsibility to Prevent Genocide. Oxford University Press.

Young, J. (1993). The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning. Yale University Press.

by Amy Fagin | Dec 12, 2016

“And seeing him sit day after day, sinister, silent, twisting his rope to a future purpose of evilness…I sense the charred-wood smell again…of charred-wood-midnight-fear…knowing that nothing is impossible…that nothing is impossible…that anything is possible…that there is no safety in words or houses…that boundaries are theoretic…and love is relative to the choice before you…”

Anne Ranasinghe, Holocaust Kindertransport survivor, married Sri Lankan Dr. Don Abraham Ranasinghe in 1949. Anne received several literary awards, including one in 2007, The Sri Lanka State Literary Award for lifetime achievement.

The opening ceremony address to the WINGS International Conference on Arts and Reconciliation, November 7th – 9th, 2016 was reserved for this distinguished European born author whose life experience embodies the universal responsibility to understand and foster creative and collective solutions to mass atrocity.

In the words of the International Coalition for the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) a summary of the conflict in Sri Lanka reads as such: “In 1983, ethnic tensions between the majority Sinhalese (mainly Buddhist) population and the Tamil (mainly Hindu) minority in the North led to a devastating civil war. For over a quarter of a century, the Sri Lankan government clashed with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, known as the LTTE or Tamil Tigers, who fought in pursuit of an independent state. The war ended on May 19, 2009, following a major government offensive that forced the rebels to surrender. Though precise figures on the death toll are difficult to tally, the United Nations suggests between 80,000 and 100,000 casualties. Such figures remain hotly contested. During this time, different actors attempted to facilitate negotiations and establish ceasefires. Nevertheless, all efforts to create sustainable peace failed.”

Also according to this report in the aftermath of the violence and until 2013 efforts and initiatives to insure the safety of civilians, and post conflict accountability coming from the international community were undertaken by the UN Security Council; the UN Human Rights Council, the European Union and a variety of Civil Society agencies including the Global Center for R2P. While the Sri Lankan government created a national plan of action it was considered inadequate in addressing the allegations of violations of international law.

By most international accounts the politics of accountability in Sri Lanka have been deeply contentious, but the election of Maithripala Sirisena in January of 2015 has heralded a new political era. Campaign promises by this new government include commitments to restoring democratic institutions, mandates for reconciliation, accountability and transitional justice processes all of which must counterbalance overwhelming Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism. The challenges to incorporate legal, economic and cultural measures toward truth, justice and memory are multifaceted.

The partners launching the WINGS cultural festivals and academic conference include national agencies, international NGOs and EU partnerships. Citizen empowerment as the driving agent of the inaugural nation-wide festival bridge foundations in “unity and mutual understanding”. Integrated, colorful and enthusiastic sharing of traditions and opportunities for citizen diplomacy with visual and performing arts, educational events for all were organized with a distinctive air of gala and national pride.

I had the distinguished honor of participating as a delegate at the three-day conference held in the capital city of Colombo, November 7 to 9, 2016.

The themes of the international conference focused on the Art of Dissent, the Art of Connecting and the Art of Witness and provided a sturdy manifesto with which to engage academic and arts expression and dialogue to better understand the challenges of post conflict reconciliation processes and case studies domestically and internationally.

The dignity and enthusiasm of and for this international collaborative event was palpable. Respect for the complexity of the issues at stake, and strategies for moving toward reconciliation for all Sri Lankans were directed effectively with the tripartite mission of Connecting, Dissent and Witness. Inclusiveness of all members of society was strategic and group focused. Tackling the sensitive issues of post conflict reconciliation can be fraught with competing claims of truth and memory. Focusing on the Art of Reconciliation allows for personal interpretation and reflection of subjective and individual experiences while adopting a collective directive. The ambiance was set tactically and tactfully toward a unified country with citizenry establishing control of democratic processes. Love and devotion to the singularity of this island nation was unabashedly present. All too often the emotional palate of an academic conference is unwelcomed, poorly understood and haphazardly incorporated into conference themes. By framing the presentations, discussions and atmosphere specifically as an expression of art, the character of the dialogue assumed an ambiance of collective observation, respectful listening, collaborative and creative problem solving.

Presentations included a wide array of domestic approaches and international case studies in political and cultural dialogue, peacebuilding and the unique challenges that various post conflict countries face in transforming violence into truth, memory and justice.

Of course I was not able to attend every presentation, and like all conferences, competing interests meant that some of the fascinating presentations I was not able to observe. There was one presentation, however, that I was not about to miss and proved to be a divinely delectable approach to the art of reconciliation through “Culinary Diplomacy” (Professor Asoka De Zoysa).

The art of cooking as a “framework for exploring gastronomic culture and practice across the ethnicities of the island, including regional, spatial, and familial influences over family culinary practices in Buddhist, Hindu and Islamic traditions” delivered a fascinating and truly delightful window into the everyday and ceremonial realms of cooking and eating around the island.

The nation is undoubtedly in the throes of wrestling with legacies of deep and painful divisions, economic and political inequalities and mass atrocity crimes that cannot be patched over with denial based unification. Conversations are delicate and nascent with regards to comprehensive approaches to reconciliation that will satisfy the tripartite missions of truth, justice and memory. It is absolutely clear however that Sri Lankan citizens are taking these matters into their own hands and have voted firmly for a future with democratic principles as a foundation for moving forward. I was privileged to witness this artfully organized conference which has demonstrated to the world the quintessential splendor of this island nation and a vision of a future that all Sri Lankans can share in.

Featured image: XKillSwitchXxx, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

by Amy Fagin | Sep 2, 2016

2016 marks a milestone anniversary year for Argentina. Forty years ago this country was thrust into a period of state organized extreme violence precipitated by a “golpe de Estado”on March 24th punctuated by kidnappings, mass arrests, torture, and murder and operation of over 600 clandestine detention centers. An estimated 30 thousand citizens were summarily executed, assassinated or “disappeared” during this military dictatorship until its collapse in 1983. The official name for the state driven terror was “Proceso de Reorganizacion Nacional”

(National Reorganization Process) which euphemistically belies the fear instilled nationwide by the military junta lead by Lieut. Gen. Jorge Rafael Videla.

The term “Dirty War” is widely used internationally to describe this era, but on Argentinian streets conversations reveal a consternation with this vernacular. The lexicon insinuates, they will tell you, that systematic authoritarian repression and mass murder is justified by the notion of civil “war” and validates government actions for those years better defined as state driven terrorism.

This past March 24th, now marked as an annual day of “Remembrance for Truth and Justice”, U.S. president Barack Obama visited Argentina attending a commemorative ceremony with Argentina’s recently elected president Mauricio Macri at Parque de la Memoria. Conciliatory words by Obama did not appease the icons of Argentine justice: Las Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, who reminded the global community of the classified intimacies that the US government provided by backing this military junta. Obama promised to release military and intelligence papers after his term of office. Perhaps a shift in international dialectics for this era in Argentine history more accurately described on Argentinian soil as an era of “State Terrorism” will take root.

I struggle to exact a concise “lexicon” for this brief article upon return from the travel seminar “Modernization, Mass Atrocity and Memorialization” to share “new vocabulary” with the genocide studies community. Our tour encompassed three major cities specifically to visit prominent ex-clandestine detention centers now operating as public memory sites, to interview representatives of institutions working with public memory initiatives, archiving and documentation of state crimes, education and legal proceedings on behalf of the victims of this era of state criminality. The goals for this visit were to broaden an understanding of the influence of global popular initiatives dedicated to ensuring truth, ensuring justice, and ensuring memory were well served, for these processes are the language of democracy.

Less than a week before our arrival in Buenos Aires 87-year-old “Madre” Hebe de Bonafini was ordered under arrest. Bonafini, one of the founders of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, defied a court order to give evidence regarding embezzlement in a case (she is not personally under accusation for).

This political development set the stage for our scholar’s tour.

On Thursday, August 11th, the day after our arrival, the 2000th March of Las Madres de la Plaza de Mayo was underway. Thousands of marchers were boisterously celebrating this 40 year milestone of unrelenting civil resistance and popular mobilization on behalf of representative democracy. Their influence has helped to shape democratic processes in Argentina.

Pictured to the right is the main hall of E.S.M.A. in the former “Casino de Oficiales,” which functioned as a central clandestine detention center in Buenos Aires. As many as 5000 men and women were detained here, many of whom “disappeared,” thrown alive into the Atlantic Ocean currents.

Pictured to the right is the main hall of E.S.M.A. in the former “Casino de Oficiales,” which functioned as a central clandestine detention center in Buenos Aires. As many as 5000 men and women were detained here, many of whom “disappeared,” thrown alive into the Atlantic Ocean currents.

Today E.S.M.A. is a public “Sitio de Memoria” providing a plethora of cultural and educational initiatives for truth, justice and memory.

In addition to visiting E.S.M.A. and Parque de la Memoria in Buenos Aires, we met with the capable staff of Memoria Abierta, a foundational consortium of human rights organizations operating in the ESMA complex and journeyed to the memory site known as El Ex Olimpo. This institution is a dignified memory site and former clandestine detention center, operating outside of the city center. Here an awareness of this site once operating as a secret prison is visceral. The life histories of each of the “disappeared” who were detained here are remembered personally as neighbors and relatives. Though this site primarily serves a domestic audience its very regional dimension conveys a physical force of the unit as a detention center as well as the weight of its responsibility now, as a memory center.

We spent one morning at the studio of noted artist / activist Marcelo Brodsky whose iconic publication “Buena memoria” internationalized the plight of Argentinian families and their personal tragedies and terrors woven into the fabric of daily life under military dictatorship.

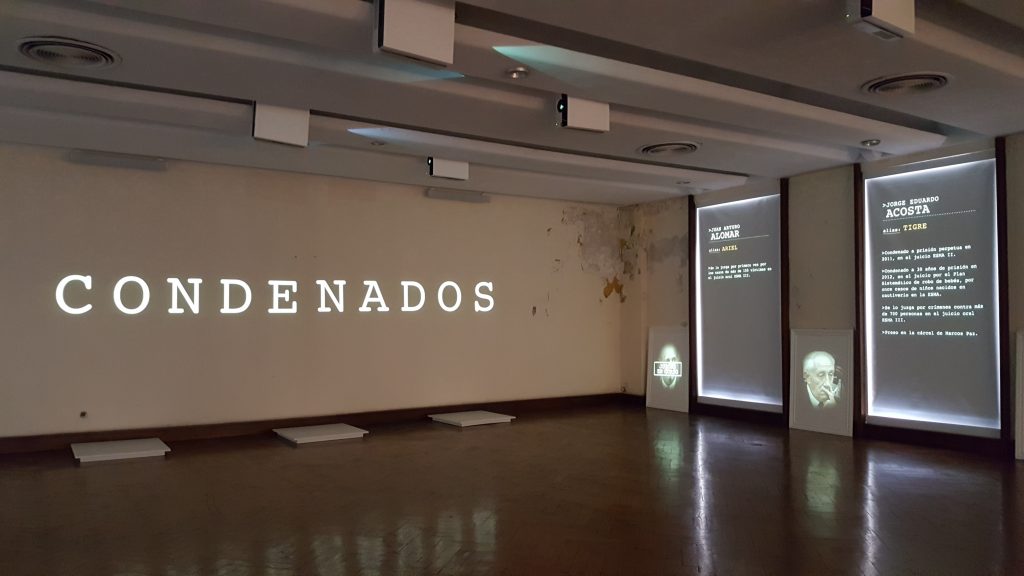

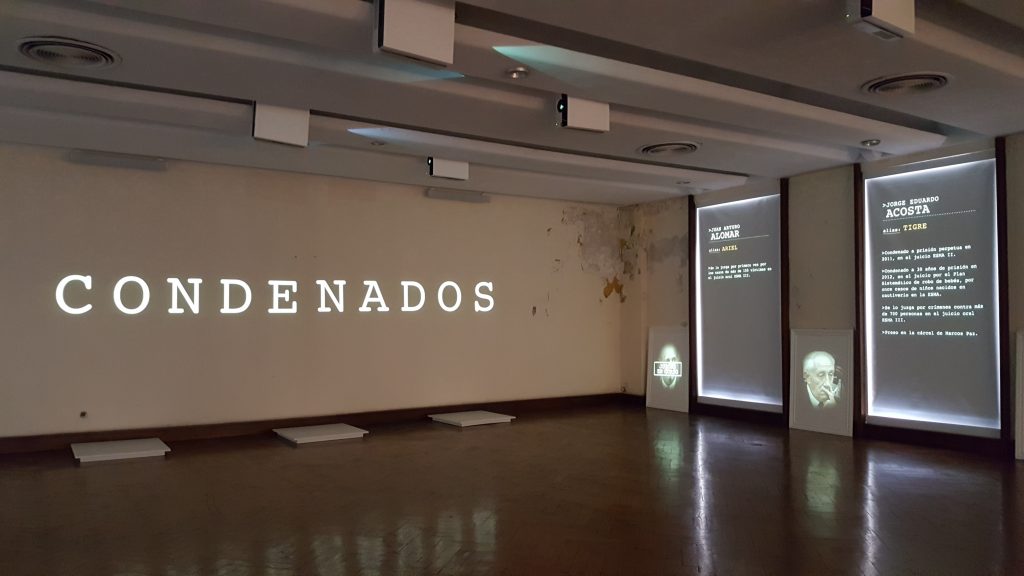

Our journey took us to Rosario to the first Museo de la Memoria established in the country, and then to Cordoba to witness the tireless work of the “Comision y Archivo Provincial de la Memoria de Cordoba”. This center provides invaluable services enforcing the legislative enactment known as the “Memory Act” (9286 Act) in 2006. Located in “D2”, a former detention center and the Police Intelligence Department of Cordoba, D2 is now a public memory space. The activities of this organization are truly remarkable and cover a wide array of activities in the areas of investigation; education; law; preservation and a myriad of civic and cultural memory initiatives. The “Comision” also maintains two other central former detention centers La Perla and Campo de La Ribera.

The histories of which house the day to day stories of a people paralyzed and terrorized by an imposed authoritarian “junta” diabolically re-defined as “government”.

Tomorrow, the 25 of August, the Dia de la Sentencia arrives in Cordoba where the “Mega Causa” trials against state terrorism completes its hearings. Summons and sentencing are set for 11:00 am.

The lexicon of democracy in Argentina begins with a capital “D.”

by Amy Fagin | Jan 3, 2016

Sponsored by the Liberation War Museum, Dhaka, Bangladesh

At 40,000 feet, flying from Dhaka to Dubai the Himalayan Mountain Range stretches from horizon to horizon, like a row of perfect white teeth in the cosmic mouth of Krishna. This parting vista seems a fitting farewell to my extraordinary journey into the educational aperture of the Second Winter School of the Center for the Study of Genocide and Justice.

Forty students and professionals who represented eleven universities, and the entire geographic area of the country, participated in this week-long intensive located at the conference campus center Proshika HRDC Trust. Participants from the disciplines of Law, Media, History, Women and Gender Studies, Victimology, Peace and Conflict Studies and English were represented with the largest percentage reserved for legal students and professionals.

The Liberation War Museum (LWM) was founded in 1996, the same year that the Awami League (one of two largest political parties, and current governing party) returned to office. The years succeeding this victory have been tumultuous and polarizing with political and citizen demonstrations, strikes, assassinations, natural and man-made disasters along with significant achievements in democratic processes. Undeniable in its strength is a huge and irrepressible youth movement dedicated to embracing the ideals of the Liberation War, and for advancing the quality of life of the citizens of the country. The LWM’s creation of the Center for the Study of Genocide and Justice has harnessed this enthusiasm in the academic and professional aspirations of the country’s next generation with the lessons learned from their history of genocide, and victory of liberation.

The Second Winter School offered an expanded curriculum from the previous year’s focus, with certificate training for its participants. The academic objectives for the first day of the program included the concept, theories and introduction to genocide and its definition, classification and legalistic elements as applicable to the International Crimes Tribunal / Bangladesh (ICT BD).

Day two focused on the history of the genocide in Bangladesh and the justice processes that have been adopted since 1971 including the important International Crimes Tribunals Act of 1973 and the establishment of the ITC BD in 2009 and its proceedings. An introductory landscape of the chronology and geography of international episodes of genocide, presented by yours truly, opened the sessions for the day.

Impressive, compassionate and passionate presentations delivered by deeply esteemed professionals such as Supreme Court Barrister Tureen Afroz, now serving as prosecuting attorney on the ICT BD courts, provided a background in the establishment of the ICT BD. I must here give comment to the international community’s criticisms of the trial proceedings, articulated for this article by Human Rights Watch. HRW posted on November 15, 2015, quoting Brad Adams, Asia Director: “Justice and accountability for the terrible crimes committed during Bangladesh’s 1971 war of independence are crucial, but trials need to meet international fair trial standards. Unfair trials can’t provide real justice, especially when the death penalty is imposed.” In addition Adams says: “The accused in all these cases were allowed a minuscule fraction of witnesses, counsel were regularly harassed and persecuted, defense witnesses faced physical threats, and witnesses were denied visas to enter the country to testify.”

I was asked many questions during the week from emerging legal professionals regarding these sensitive and very complicated issues. Not being a lawyer, nor deeply versed in international criminal law, or Bangladeshi criminal law, I could only offer my knowledge of capital punishment as it is practiced or abolished independently by individual state law in the USA. The complexities of these and other domestic court proceedings coping with mass atrocity crimes waged against whole populations, as well as the roles of domestic and international criminal law are, to be sure, nascent areas of study and practice world-wide. Establishing best practices in trial proceedings, whether domestic or international is only just emerging. The International Criminal Court began functioning just a little over a decade ago and is “intended to complement existing national judicial systems”. National judicial systems established, themselves, to bring their most heinous mass atrocity criminals to justice before their citizens, is also still adolescent in development. According to the International Bar Association’s evaluation of the ICT BD: “Many civil society groups, victims and their descendants have steadfastly backed the war crimes trials, which they feel are a crucial process that denied them for over 40 years.” What I can say about this experience, with complete authority, is that everyone participating in this educational experiment in the study of genocide and justice were personally and professionally compassionate, honest and dedicated to upholding best practices. Each individual demonstrated an astute willingness and commitment to fair trial standards.

On day three the group explored the ongoing relationships between the ideals of international criminal law and Bangladeshi demand for justice in the aftermath of genocide with esteemed professors’ Dr. Ashfaque Hossain and Sheikh Hafizur Rahman Karzon, respectively of history and law based at the University of Dhaka. In the afternoon I had opportunity to work with the students in an interactive workshop: “Community Conversations, Global Perspectives Beyond Genocide” where we explored “Visual Thinking Strategies” to learn more about specific case studies of genocide as expressed and interpreted through art. Defining and protecting members of a human group, typologies and discussions on the legal implications of “genocide” verses “crimes against humanity” met with lively debate.

Heartfelt testimony was delivered by Julian Francis, who was working with Oxfam during the tragic days of the Liberation War in several refugee camps. The reality of the suffering of the victims’ of mass violence, that Julian portrayed, are the stories of these young adults’ parents’ and grandparents, aunts and uncles.

The case study of Indonesia was a focus of multimedia attention with a series of presentations including two important films “The Act of Killing” and “40 Years of Silence” as well “Thinking Through Art” and an investigation of memory and memorialization with a review of the “1965 Park” project; a controversial experiment in memorialization of a mass atrocity that divided the community it was designed to honor. In the short span of time that the group had to work with the complexities of this case study a deep level of understanding was achieved by all through this multidimensional examination.

Day four covered the issues of: Socio-Legal Significance of the ICT BD Judgements, Transitional Justice Processes, and Memory, Mass Atrocity and Memorialization.

Early morning on day five, students visited the Dhamrai Killing and Battlefield where they met with Bangladesh independence fighters (known domestically as “freedom fighters”) and later delivered multi media group presentations covering this impactful investigative experience. The connection to the history of the nation was made evident and current, even if this participant could not understand Bangla.

My last day with this group was a revelation to me in learning about the impact on the lives of victims of sexual violence from this era, efforts at reparation, protection and the challenges of investigation of these crimes that carry stigma to the victim. I also had the great privilege to meet several women who represented this generation of war babies and children of victims of “intellectual killings” and realized on a visceral level the generational influence that violence has to individuals, families, communities and nations.

Upon my arrival to Dhaka the early evening hours were a cacophony of celebration of the 45th anniversary of independence. Every sidewalk was full spectrum with brilliantly dressed Bangladeshis rejoicing in their independence and honoring their war heroes.

On the road from the airport to my hotel, downtown Dhaka celebrants stretched from horizon to horizon, like living garlands of Hawaiian leis (floral necklaces for the gods and one another of love and affection). This arrival vista seems a fitting greeting to my extraordinary journey into the blossoming of the 2nd Winter School of the Center for the Study of Genocide and Justice.

Featured image: Mohammad Fazla Rabbe, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

by Amy Fagin | Sep 22, 2015

We, the delegates attending the Fifth International Conference on Genocide: Bangladesh and the Pursuit of Justice, February 27, 2015, to March 1, 2015, arrived at Dhaka International Airport to beautiful bouquets of flowers and swarms of hungry mosquitos. Fortunately for the international visitors the mosquitos showed a distinct preference for dining at the airport. And, if I consider the metaphor of this early dawn moment; it is a fitting symbolic crucible upon which the next week of progressive international dialogue and domestic political extremist brutality and backlash intertwined.

The Liberation War Museum (LWM), our conference organizer (which includes the esteemed board of trustees as well as a cadre of intelligent, inquisitive, dedicated and organized volunteers), has genuinely blazed a path for a nation-wide scholastic platform for justice processes public education and victim rehabilitation and reparation in post conflict justice, not only in the case of Bangladesh, but in linking the case of Bangladesh to international cases around the globe. To be sure, the challenges are huge for this young nation with a literacy rate of 57.7 percent and 72 universities serving the approximately 160 million citizens. But the heroic efforts and vision of the LWM, since its establishment in 1996 has forged a truly national agenda in the history of independence in Bangladesh and an emerging interdisciplinary educational platform in genocide studies at their new Centre or the Study of Genocide and Justice.

My invitation as a delegate to the conference was by way of a tenured professional friendship with Mofidul Hoque, executive director of the LWM, whom I came to know some 15 years ago when reaching out to the museum for information about the ‘71 genocide.

The conference was attended by 19 international delegates and well over 100 students and citizens; and what was crystal clear about the attendees was their enthusiasm, commitment to justice and efforts to learn and understand difficult and often paradoxical truths about genocide and post conflict social issues. This is a nation with 44 years of personal experience resurrecting social normalcy in the aftermath of attempted annihilation. So as delegates we were distinctly privileged to learn about the experiences and efforts of the Bangladeshi community, and especially the efforts of the Liberation War Museum in creating public, academic and judicial platforms in “the pursuit of justice”.

The focus of the conference centered around formal and informal paths toward justice processes in the aftermath of mass atrocity, domestically and internationally with an emphasis on dialogue, discussion and finding links and lessons learned to advance these processes within Bangladesh and the region as well as to address unmet needs of the population. The current judicial hearings now underway in Bangladesh (International Crimes Tribunals of Bangladesh ICT-BD) and comparative practices, theory and history of other international trial processes which are unfolding around the world, post conflict, was a central topic of presentation by international and domestic professionals. Contributions from esteemed international judges from the Argentinian Tribunals, the ECCC, Cambodia and the, ICT-BD presented historical overviews and their professional experiences of each of these proceedings; and importantly met together in informal sessions where practices and legal codes were compared in the light of international standards of legal conduct and judicial proceedings.

Broader issues of reparations, social and health related support for victims, with emphasis on crimes of sexual violence and remedies for survivors also played a significant role in the conference proceedings. Domestic media discourses, gender stereotypes, representations and realities of the Birangona (war heroines) with discussion on rehabilitation practices domestically and internationally were presented by esteemed delegates representing domestic and international efforts and challenges. A special and moving session was established to listen to the “Victim’s Voice for Justice” which, for me, was especially powerful as these dramatic testimonies reveal a universal and deeply emotional appeal to take these matters to heart.

The roles of the media, the arts, memory, memorialization and memorial sites, research and documentation, scholars’ and religious organizations, policy think tanks, public education, as well as the roles of the United Nations and the International Criminal Court were all subjects for presentation and evaluation.

On the day of our arrival, one day prior to the conference, several of the international delegates were treated to an afternoon tour of Dhaka’s “sites of conscience” including the LWM’s current site located in a modest 3,000 square meter, two story building, and a walkthrough of the new “under construction” LWM; an eye boggling 30,000 square meters. Skeptics may have to acquiesce their reservations because, in this writers’ estimation, the vision, dedication and influence of the humble LWM board of trustees to fashion the new LWM as a people’s museum and a beacon of justice and democracy in a tolerant and pluralistic Bangladesh is inexorably underway.

And make no mistake about the steep challenges that lay ahead for this intrepid and globally savvy board of trustees as the daily paper revealed the next morning after our arrival. Humanist, Bangladesh born, US citizen and popular blogger Avijit Roy was violently massacred while visiting the Ekushey Book Fair not two hours after we, ourselves meandered the stalls and sights of the packed fairgrounds. His vicious street murder, charged to ”fundamentalist blogger” Farabi Shafiur Rahman, unleashed a backlash of protest of secular activists who took to the streets in massive demonstrations at the outset of our conference deliberations. The bitter divisions between secular and conservative Islamic national trends in freedom of speech and pluralist tolerance drew the curtain to the stage setting for the conference and the perplexing paradoxes of this young nation.

On my taxi ride to the airport at 4:30 am, our intrepid driver’s car console caught my eye with a hardcover book written in Bangla with a photo portrait of Adolf Hitler prominently on the cover. The book was a copy of Mein Kampf translated into Bangla. Had it not been so early in the morning I would have taken the opportunity to learn more about how the driver came to learn about this work and what he thought of it. I also would have recommended that he visit the traveling Anne Frank exhibition currently installed in the Bangladesh National Museum (BNM) and co-organized by the LWM, the BNM, and the Anne Frank House. But I was short of cognition and coffee that early in the morning, and was thereafter whisked away to Istanbul and then final destination Boston.

I am, overall, heartened by what I observed this past week in Dhaka, in spite of the tragic and terribly vicious violence we were so close to. Bangladeshis have matters firmly in their hands and a profound commitment to peaceful, democratic processes are a native virtue steeped in their ancient history with the likes of King Ashoka as national legends. I am privileged to have had the opportunity to receive this “bouquet” of domestic insight and action in jurisprudence, respect and concern for pluralism, tolerance, interest and adherence to international standards and practices in genocide tribunals academic and public education and victim rehabilitation that is the vision of the LWM. In spite of the terrible sting of the murder of a beloved countryman who represents the causes of “secularism and science” I do believe that Bangladesh is emerging as a leader for the entire region with the establishment of the agendas set out at this conference. Joie Bangla!