by Amy Fagin | Oct 8, 2014

The valley carved out by the Mbirurume River in the Western Province of the “Land of a Thousand Hills” was a scenic spot to get out of the car for a breeze and joke with the local kids.

Our driver, Didier, grumbled as we labored our way up to the knoll to where Nyange Church is located, the site of a uniquely grizzly massacre during the ’94 genocide. We took a jumpy turn onto a red dust road and arrived at the quiet, and closed, memorial site.

Through the gate the floor of the original church looked neatly re-cobbled after having been bulldozed into rubble with 2,000 refugee congregants inside, back in April of 1994.

The “cellar hatch” mass graves on the memorial site gave the eerie impression that the dead buried in these bunkers still have a lot on their minds and an open invitation to “c’mon down.”

This was our first visit to Nyange Church. But our driver knew that the stories, now muzzled, under these “cellar hatch” graves had much deeper reflections to illuminate the events in April of 1994. And on the road back from Kibuye, along the same highway, Didier drove us back up to Nyange Church, and this time was determined to find the self-appointed guide to enlighten us “dark tourists.”

On this Sunday morning the new church shelter, which is erected beside the memorial site, was vibrant with the rhythms of the morning prayer service and bustling with irreverent children who crowded around the car to see the “Mzungu” while Didier went looking for Aloys Rwamasirabo, the keeper of the memorial, to deliver us a guided tour of the site.

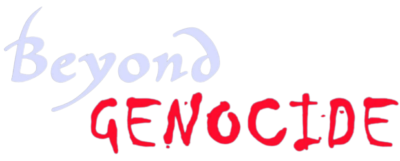

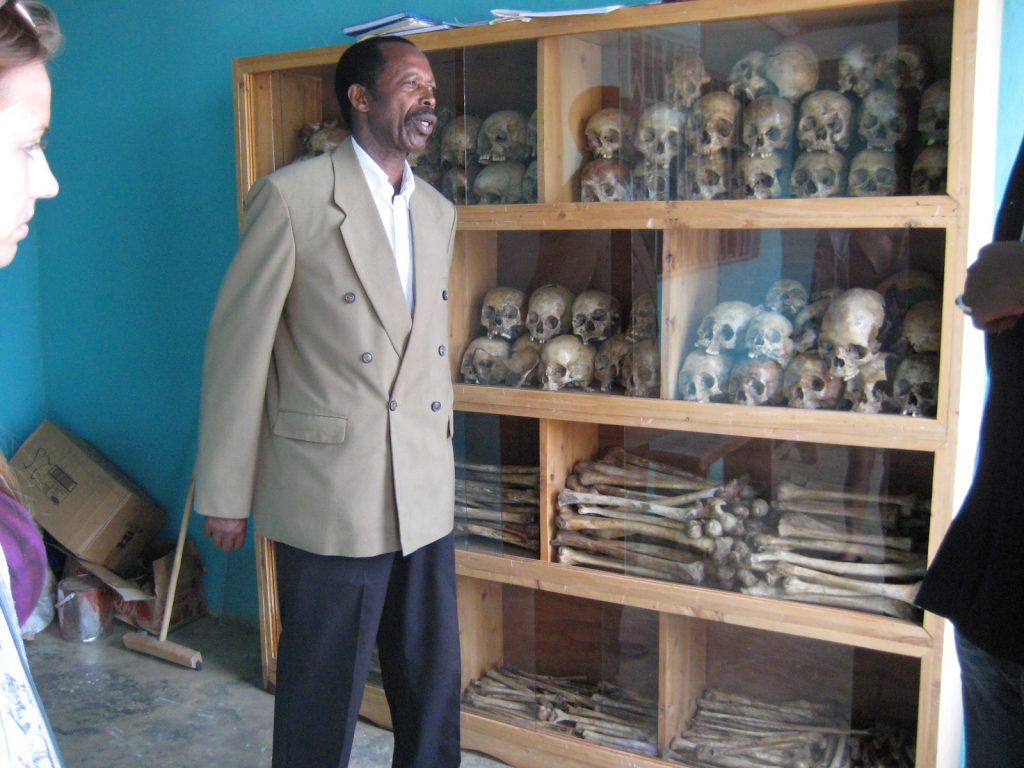

Aloys ushered us into the vestige of the Parish priests’ preparation room where the depth of the tale of Nyange Church was revealed to us among the carefully arranged bones of murdered congregants.

Aloys did not speak English, but our driver doubled as translator and we listened to the tale, first in Kinyarwanda, then in English. The rhythm of the story reverberated with the rhythm of the drums and song just outside the memorial gate. The effect was penetrating.’

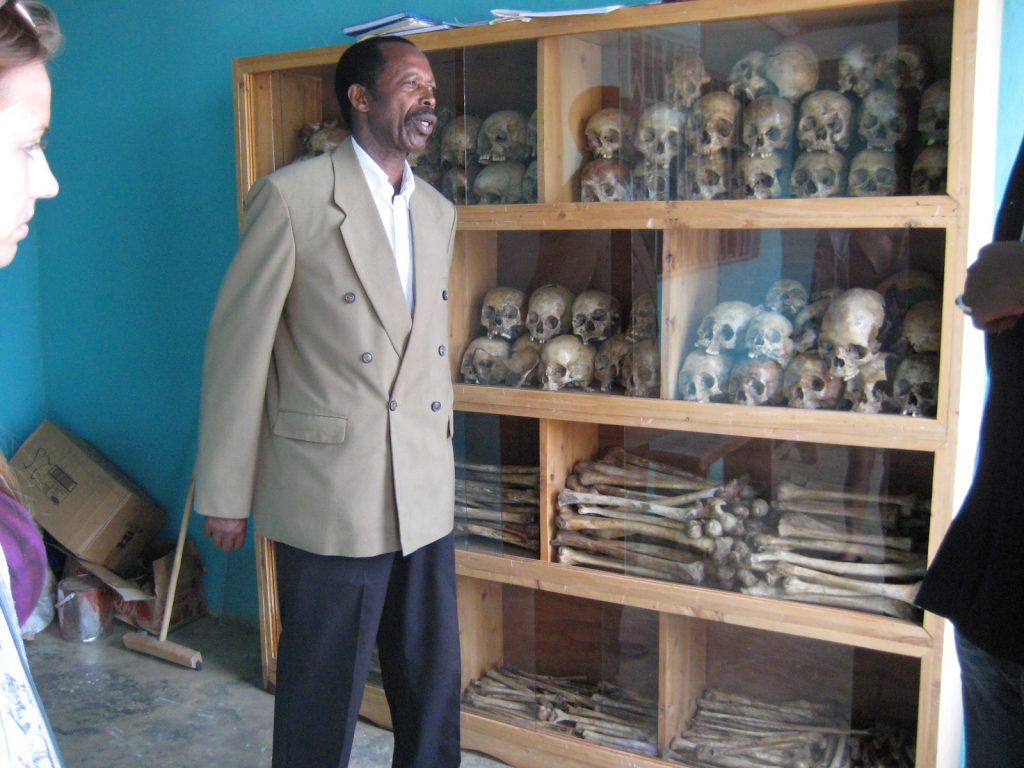

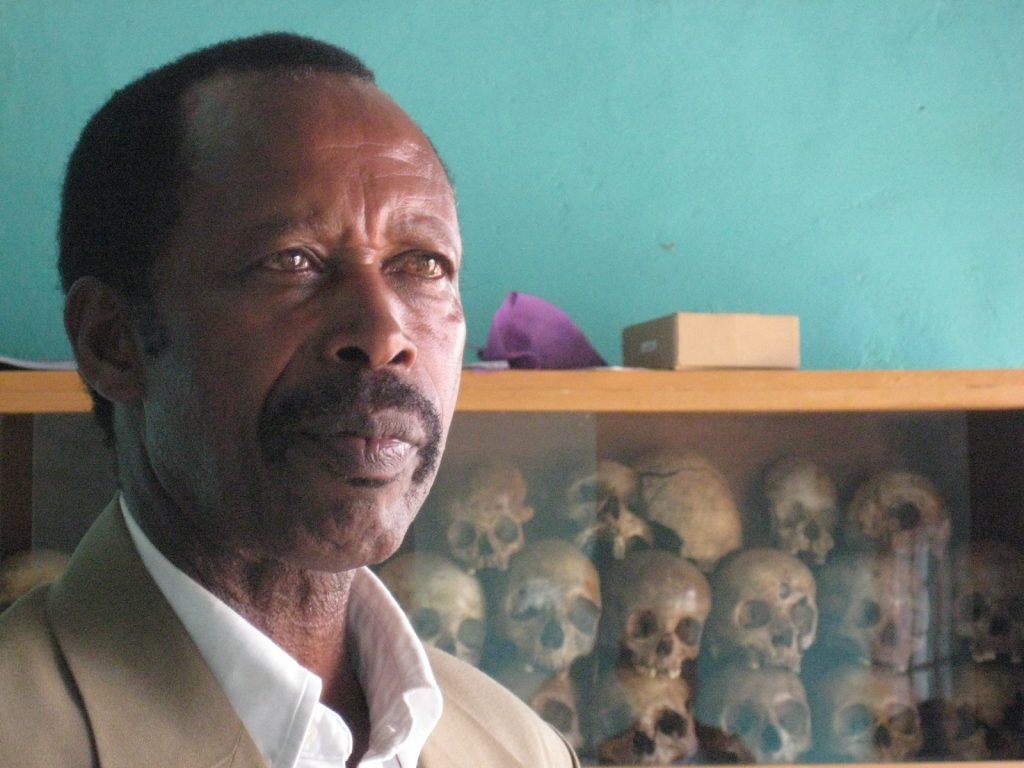

I asked Aloys, through Didier, if he minded if I took his picture as his story unfolded.

My students grimaced at my bad taste. However Aloys did not seem perturbed by the infraction and proceeded to inform us of the gruesome chronology of the days in mid April, ‘94 when the church was encircled by the Interahamwe and other militia and the refugees inside were massacred and the building ultimately bulldozed into the ground with parishioners buried alive.

I asked Mr. Rwamasirabo about his personal story. He invited us into the tale of his family, and alluded to the terror of the community and those that were held hostage in the church. He told us that nine of his children, his mother and four sisters, who were all in the church for safety, had all perished during these terrible, no, cataclysmic hours. I asked if he would recite each name, so that I could record all the names of his family members who were murdered. Didier wrote down each name for me, and their proper spelling, in my journal. (I have the notebook with the names of all of Aloys’ family members open to the page of their recording by me now as I type.)

This naming; the sacred and time immemorial ritual to honor the dead was a moment of genuine sharing of grief and condolence for us all. I understood, if only marginally, the personal burden of suffering and loss that Aloys has carried these 20 years, now.

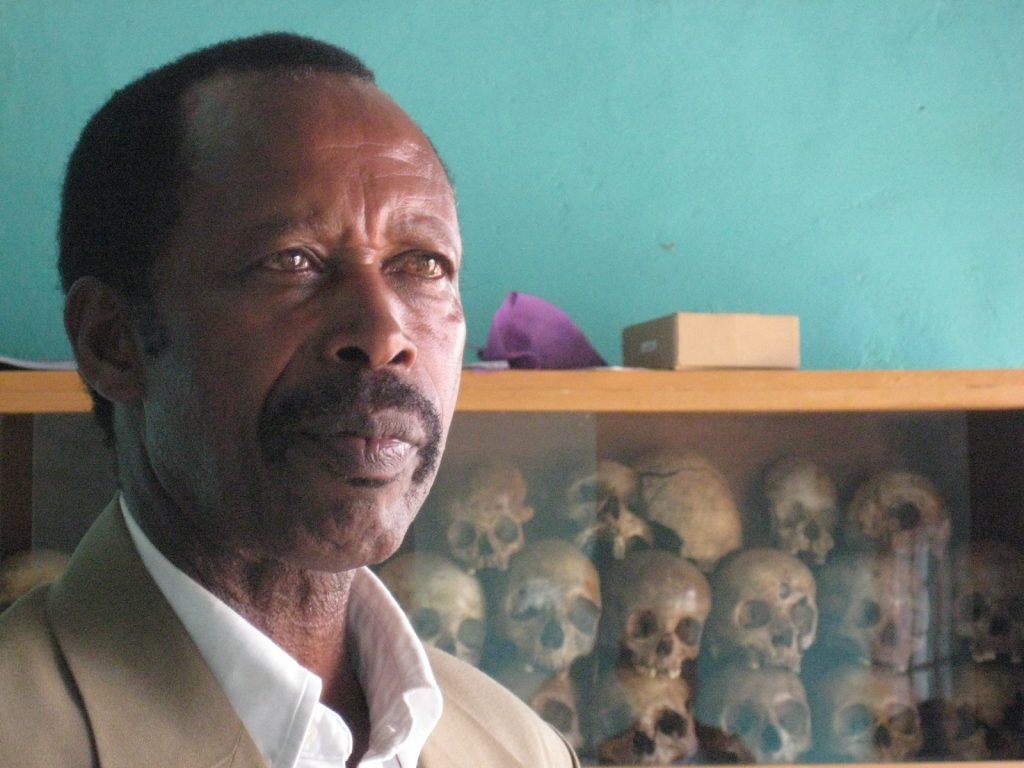

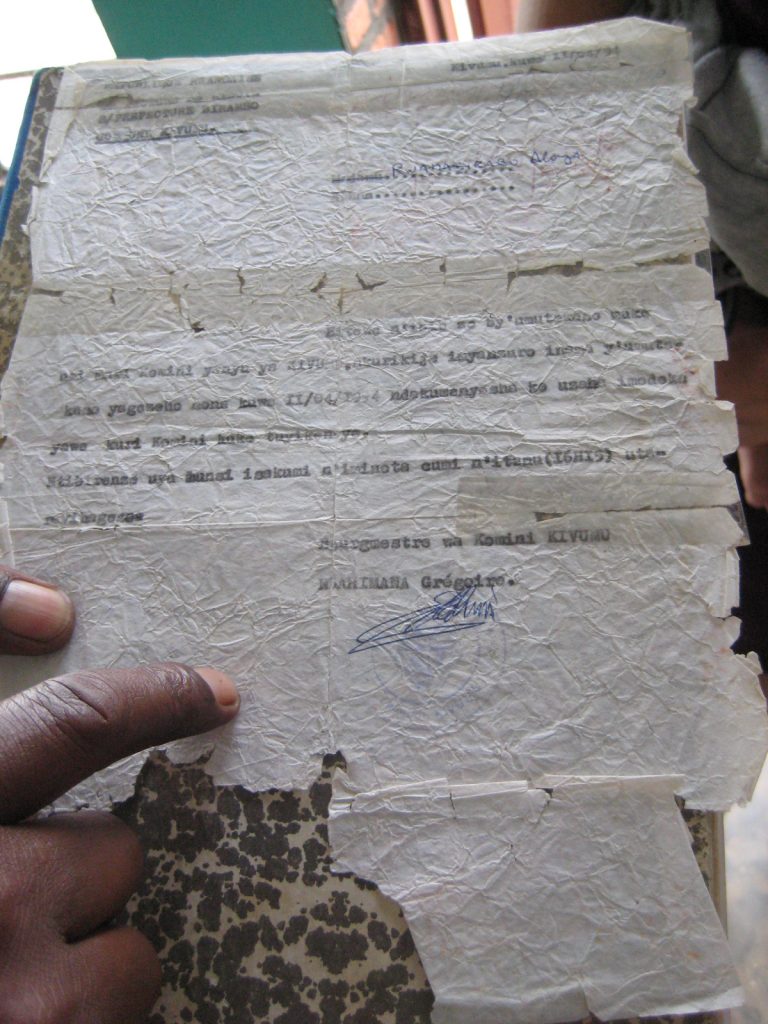

Other important details of Aloys’ narrative were translated for us. He was almost captured himself, when the district prefecture letter requested that he bring his car to the compound to be used for “official” purposes. He understood the deadly instructions of the letter for his life, and narrowly escaped plans for his murder.

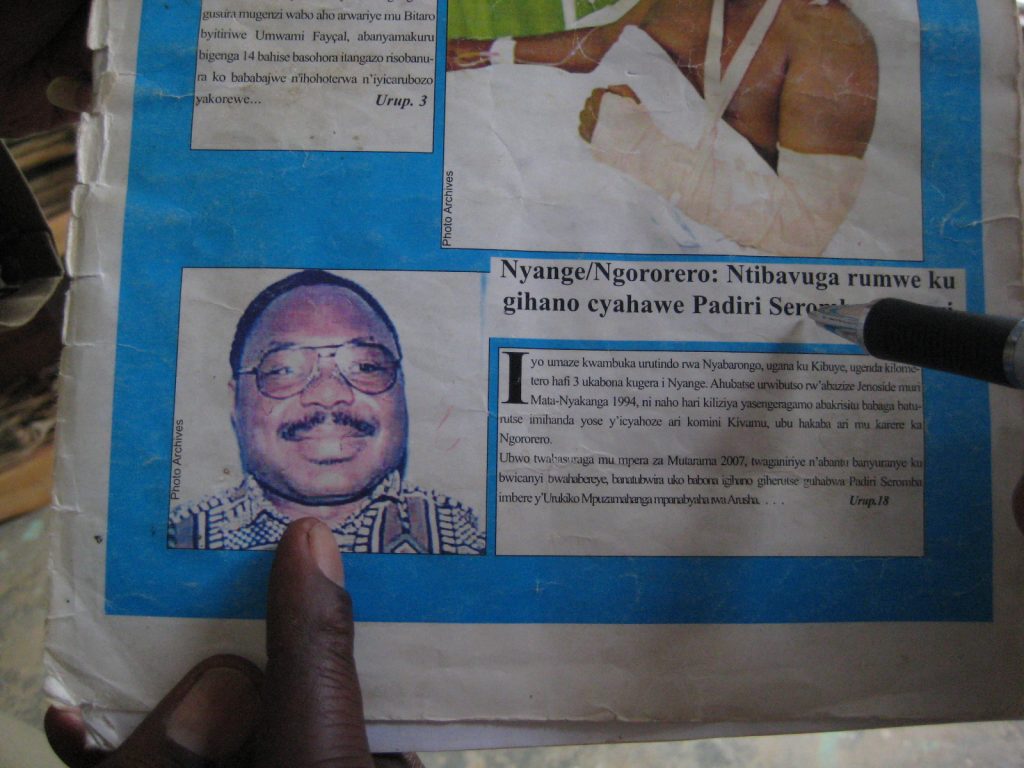

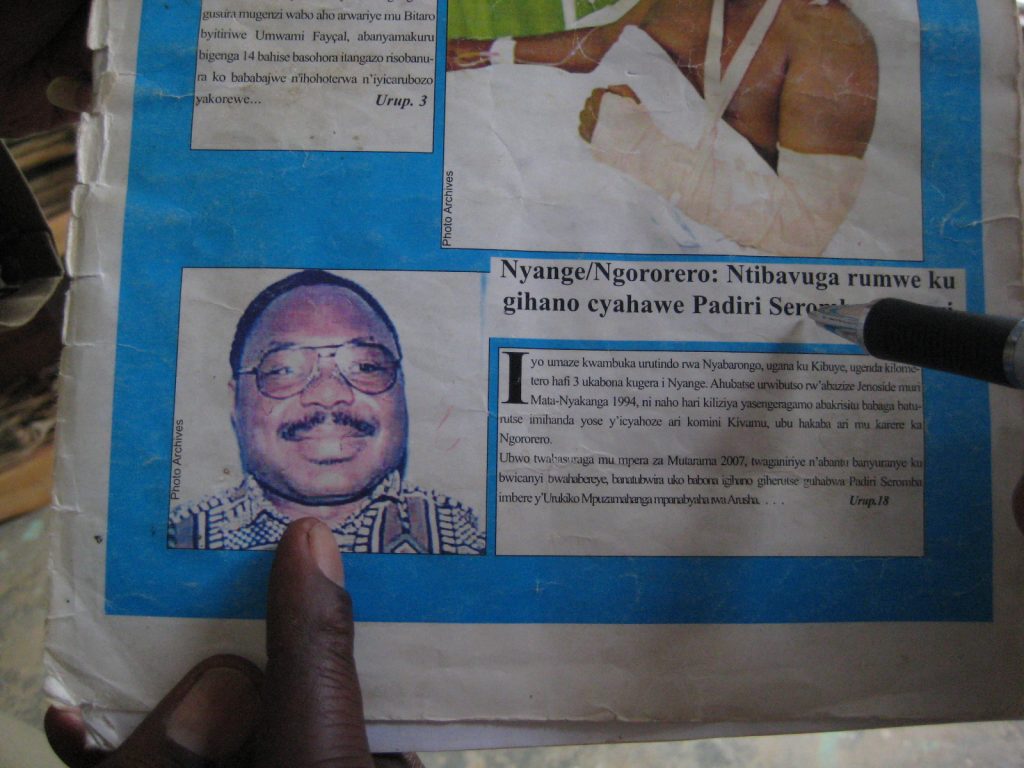

Through translator / guide Didier, Aloys also implicated the crimes of Nyange Church’s Priest Athanase Seromba, who was convicted of aiding and abetting genocide and crimes against humanity by the ICTR in 2002. Aloys informed us that he was singularly responsible for the ordering of the bulldozing of his church while his congregants hid inside. Seromba is serving a life sentence in Akpro-Missecrete prison in Benin.

Aloys concluded his story about the church today and the memorial site that he oversees. After the atrocities ended he tells us that the community was planning on building the new church right over the rubble of the massacre site. Aloys insisted that a holy church cannot be sanctified where the feet of the congregants tread on their murdered townsfolk. He initiated and oversaw the building and maintenance of this sacred memorial site and regularly guides visitors in and around the memorial.

Coreopsis and Chamomile grow around the memorial grounds today.

The fractured frame of a once radiant stained glass church window is propped against the remaining bricks of the destroyed church.

As we bundle back into Didier’s car he quietly mentions to me that he had never heard Aloys’ tell his personal story to the other visitors that he takes, regularly, to this site. I was humbled and very grateful to hear this intimate revelation.

And I share this deeper reflection of my heart, to you, across oceans, over time, transcending the miniscule prisons of our individual lives and down into those cellar hatch graves where this story is the point at the center of the universe, the place where the Tao reveals “heaven and earth meet” and our existence is one.

We climbed back into the sultry beauty of the West Province hills as the church service rang out in rhythm and sacred song.

by Amy Fagin | Sep 3, 2014

The following is a review of Native America and the Question of Genocide by Alex Alvarez (Rowman and Littlefield, 2014).

This review and analysis of the complexities and scale of atrocities perpetrated upon Native America from the 16th through the 20th centuries frames a treatise around the current and debatable question of genocide. In the book’s concluding paragraph, it is scholar and historian Paul Bartrop who is given the last word on to the warrant of portraying the accuracy of the complex atrocities perpetrated against the native populations of America. This and future generations are the bearers of this responsibility, and to whom this effort matters most.

The work is organized as a chronological and geographical overture of the Native populations of the Americas extrapolating on the ambiguity that the definition of genocide represents in the context the various crimes associated with mass annihilation: massacres; exterminations; crimes against humanity and genocide as well as war, disease, expropriation and forced assimilation over the past several centuries on said population.

Alvarez’s work is a plain-speaking introductory assessment of the perennial debates surrounding the term genocide and its application, legalistically and conceptually, to a selection of relevant Native American experiences during and after colonial invasion and expansion. He weaves together the origins and modern life of Native Americans as they emerge from pre-history to populate the Western Hemisphere and struggle to maintain their threshold from the onslaught of European colonization.

His overture begins with the arrival of the first peoples to the Western Hemisphere from what is believed to be Siberia, some 12,000 to 35,000 years ago; the various tribal groups inhabiting the lands from Beringia to Tierra del Fuego and their first encounters with Norse and Viking voyagers. The chapter shifts abruptly into a survey of the perceptions and mythical ideals of the Noble Savage (20) whereby Alvarez conjectures that this myth contributes in equal measure to the ideologies that ignited conflict and eradication of Native Americans as do negative stereotypes.

Chapter 2 shifts the readers’ attention to an introduction of the theoretical principals underlying the term genocide in order to establish and “apply the concept of genocide to the experience of the indigenous peoples of the Americas” (25). The historical formulation of the name; Article II of the United Nations (U.N.) Genocide Convention; and a relevant breakdown of the component parts of the definition are called into play to provide a platform for interpretation and application to the post-contact Native experience. Here Alvarez speculates on the shortcomings and politically designed limitations of the U.N. definition and its pertinence in appraising the history of Native Americans as genocide. How the contested debates around the definition of the term apply to a “potential larger pattern of intentional violence aimed at extermination of the tribes involved” (39) are evaluated in this chapter.

In chapter 3 the interactions between Natives and Europeans are couched in a sociological construct of destructive beliefs condensed into an overview of the role of policies and practices which ideologically fueled the intolerance and violence of the first explorers. The economic underpinnings of European culture and violence are outlined as the thrust of the conflict between Europeans and Natives whereby lust for land, gold and furs of the first traders and settlers described the mentality which led to colonial genocidal processes. Reference to the inherent exterminatory nature of settler colonialism lends currency to the contemporary debates of an overarching social pattern of settler colonialism and the inevitability of genocide as a byproduct of this social-phenomena world-wide. Alvarez cautions the reader to understand that “goals and practices often changed and evolved over time as needs and circumstances changed and evolved” and furthermore that individual populations did not uniformly conform to the “destructive beliefs of structural violence” (60).

The onslaught of and vulnerability to disease suffered by Native populations is fleshed out in chapter 4. Its catastrophic impact on the lives of Native populations throughout the hemisphere and centuries is outlined as a major contributor influencing the course of events hedging the victory of colonial–settler conquest. Cases where “disease as a tool of warfare” (85), and consequent genocidal intent, are considered by population and disease type. Alvarez concludes that in understanding genocide and disease there are only isolated cases which link the conceptual framework of “genocide through disease” (87) as a major pattern of intent causing the wholesale destruction of so many Native peoples.

The Sand Creek Massacre of 1864 in Colorado opens the next chapter deliberating the causes and consequences of wars and massacres as theoretical construct of genocide and Native populations of North America. Succinct and carefully composed historical overviews of the Sand Creek Massacre, the Washita River assault, Wounded Knee, the California Gold Rush and the Pequot War are examined within the social and political context of these eras and how each incident or period of history fits the criteria of genocide.

The tragedies of the destroyed and displaced Native populations described in chapter 6, “Exiles in Their Own Land” (119), are woven into a bleak tapestry of the fates of the Navajo and the Cherokee Nations’ “horrific tribulations” (129) of forced removals and relocations experienced by some 40 plus tribes in the 19th century. Government policy, military and civilian campaigns of ethnocide are the weft and warp of a textile of tragedy whereby the author aptly conveys the measure of wrenching trauma experienced during this century by its Native populations. The question as to “whether or not these policies constituted genocide…depends on how one uses the term” (140).

In chapter 7 “Education for Assimilation,” Alvarez turns chronologically toward the end of the 19th century and into the 20th century with an appraisal of the reservation and boarding school systems established in 1882 with the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. These institutions are taken to task as a gulag (142) system of legally and militarily forced incarcerations facilitating ultimate conquest. The tactics of cultural genocide are clearly laid out in the paradoxical intentions of the dominant culture to forcibly assimilate the remaining Native groups. Alvarez posits an unambiguous argument that cultural genocide would be a prosecutable crime as it pertains to the intended eradication of Native Americans, were it to have been included in the 1948 UN Genocide Convention.

In closing, Alvarez makes a concerted evaluation of the dichotomies inherent in the term genocide as a catchall phrase for its ability / relevance in comprising the lived experiences of the Native populations of the Western Hemisphere. He determines that, ultimately, the intellectual debates surrounding the question of genocide and Native America can only surmise the reality of the people’s suffering of this era, but that this effort is summarily relevant to understanding the thresholds of the conceptual terminology of genocide.

This timely volume presents current and relevant theories and their historical underpinnings as a re-construction of Native American history in light of the question of genocide. Alvarez’s approach to this treatise is fluid to the point of turbidity however, and the reader must carefully transition, independently, between theoretical and conceptual interpretations and those historical events that serve the theoretical master. The book would be an excellent tool for discussion in a group educational platform. Chapters can be utilized individually, and combined effectively with companion readings to supplement the book’s fragmented flow and readability. Combined with relevant readings, a comprehensive analytical understanding to the question of genocide and Native America can be developed with the construct of this discourse.

by Amy Fagin | Jun 5, 2014

“Monumental” is not too grand a description of the task put before the working groups invited to the Third Consultative Meeting of the African Union Human Rights Memorial (AUHRM), April 11 and 12, 2013, at the African Union Headquarters in Addis Ababa. Lessons in contrasts, compromises, determination and irony of stark proportions were immediately apparent to this participant. My invitation to this fascinating proceeding was a result of a nomination through the venerable organization of the “International Association of Genocide Scholars” of which I am a member and currently serve on its advisory board. That is to say, I was a newcomer to the AUHRM prior to this invitation.

While my flight arrangements were being settled and preliminary information was issued to us about the project I did a little homework. The new headquarters of the African Union was inaugurated in January, 2012. The gleaming structure was built entirely with funds from the Chinese government as a gift to Africa at a cost of USD 200 million. And upon arrival at the compound I was made aware of this first stark contrast that the headquarters represents in towering over the dominantly modest construction and mushroom shacks sprouting in this city of 3.3 million (official) – 5 million (unofficial).

Before I arrived a list of the criteria to be further discussed in working groups was sent to us in recognition of 5 categories of atrocities which had occurred across the continent (for those of you new to this subject you can Google any of these issues): The Red Terror; Rwandan Genocide; Apartheid; Slavery; Civil War and South Sudan. After receiving this first introductory leaflet via email, prior to my journey, I wondered to myself…what about the Herero genocide at the turn of the 20th century? What about the Igbos who were murdered in the millions during the civil war era in Nigeria, but to name a couple of “biggies”? Why, I wondered, were these important genocides not included in the topics for discussion?

After our arrival, our paperwork included a sixth category which was added to the forums for discussion related to the 1996 Abu Salim Prison Massacre during Gaddafi Era Libya. I kept these concerns to myself prior to the conference, always cautious of my own knowledge of complicated historic events, and not being privy to any potential political paradoxes. Fortunately, after voicing my concerns at the initial round table discussions it was made clear to us that inclusion of the many human rights violations perpetrated across the continent was not finalized and was a work in progress. The emphasis of the working groups, we were told, was on the process itself and that formalizing professional contacts and helping to refine the order of this process, with compromise and patience at this juncture, was advised. I kept this valuable instruction in mind as we proceeded through introductions and later in our working groups.

Indeed, the seasoned and varied expertise, commitment and fierce determination of the participants was apparent and equal in force to the daunting mandate at hand.

In hearing the stories of survivors from Rwanda, Ethiopia, South Sudan and Libya as well as efforts of individuals working with the 25 agencies represented at the conference: such as the esteemed facilitators at Justice Africa; The World Peace Foundation; The International Coalition of Sites of Conscience; Johannesburg Holocaust and Genocide Centre; District Six Museum; Ethiopian Red Terror Documentation and Research Centre (just to name a few); it was apparent that the working groups were extremely well prepared to move the agenda forward with constructive deliberations and clear decisions.

We gathered around the foundation stone for the AUHRM after the first afternoon of the conference. This stone is located on the potential grounds of the proposed memorial, and it was here that we listened to stories of survivors of the Alem Bekagn Central Prison. The stark irony of this experience for the author and indeed, to all who participated, is the chilling fact that the prison and all evidence of its existence was completely destroyed to make way for the new headquarters of the African Union.

Featured image: Laika ac from UK, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

by Amy Fagin | Jun 5, 2014

This past weekend, my husband and I were dining with local and international friends. I was mentioning an interview I had recently heard on Harry Shearer Le-Show with Alexa O’Brien. Ms O’Brien is an independent journalist who is—uniquely—covering the Chelsea Manning pre-trial hearings. In my recollection of the interview to my guests I had voiced my concern about the virtually complete silence which the press has taken regarding this trial which challenges the foundations of a individual’s right to inform fellow citizens of activity which “would harm the country,” even if it’s perpetrated by one’s own government. My local guest looked at me incredulously, asking: “Who is Chelsea Manning?” If you, dear reader, do not already know who Chelsea Manning is, I urge you to find out a little more about this young woman / soldier who is on trial for violating the “Espionage Act” in supplying WikiLeaks sensitive State Department cables,the classified videos of the 2009, B-1 Bomber “Granai Airstrike” killing approximately 86 to 147 Afghan civilians (mostly women and children) and the AH- 64 Apache Helicopter “Baghdad Airstrike” that killed two Reuters photojournalists and a number of civilians.

The jockeying for secret court sessions in the pre-trial phases, and very sparse media coverage with the exception of Ms. O’Brien, will, all but guarantee that you will have access to little information about these unprecedented proceedings.

Private First Class Manning was arrested on May 26, 2010. In July, she was classified as a maximum custody detainee, with Prevention of Injury (POI) status, entailing checks by guards every five minutes. Her lawyer, David Coombs, a former military attorney, said she was not allowed to sleep between 5 am (7 am at weekends) and 8 pm, and was made to stand or sit up if she tried to. She was required to remain visible at all times, including at night, which entailed no access to sheets, no pillow except one built into his mattress, and a blanket designed not to be shredded. In early April, 2011, 295 academics (most of them American legal scholars) signed a letter arguing that the treatment was a violation of the United States Constitution. The public outcry of these extreme prison conditions and Coombs’ efforts, have resulted in improved conditions.

Whether the outcome of this trial recognizes Manning’s whistleblowing under the freedom of information act as the legally sanctioned prerequisite for transparency and accountability of our government or a guilty verdict of misconduct of a US army soldier’s handling of classified information, we may never find out. This pivotal trial may never become part of our mainstream news broadcasts because this “Prisoner Without a Name” has become a symbol of the silencing of information on the parts of our judicial system, government and media, and in need of our safeguarding.

Featured image: Chelsea E. Manning, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

by Amy Fagin | Jun 5, 2014

The following is a review of War, Genocide and Justice: Cambodian American Memory Work by Cathy J. Schlund-Vials (University of Minnesota Press, 2012).

For Cambodian Americans, the challenges of identity, as individuals and community, whose recent past embodies the societal fragmentation and the trauma of war, genocide and relocation is the raw material for “memory work” in Cathy J. Schlund-Vial’s publication War, Genocide and Justice: Cambodian American Memory Work.

This volume brings to the forefront the deep reckoning with history and memory manifested through the intimacies and perplexing challenges faced by the “1.5 generation” of Cambodian Americans through contemporary cultural expressions in film, literature, rap music and dramatic performance. The thrust of Schlund-Vials’ theoretical framework is revealed through her analytical treatise of these forms of cultural expression, which she evaluates in couched terms as an “attempt to remember a history of U.S. imperialism, Khmer Rouge authoritarianism, and involuntary refugee dispersal.” The clarity and depth of critical analysis that Schlund-Vials attends to with each example is impassioned, thorough, multi layered and illuminating for the otherwise uninitiated reader to the complexities and trials of survivors and their descendants in the Diaspora of the “Khmer Rouge Reign of Terror.”

The introduction sets the stage for the content of the work as an “interdisciplinary investigation into how Cambodian American cultural producers analogously (yet divergently) labor to rearticulate and re-imagine the Killing Fields era vis-à-vis three distinct and unfixed modes of negation: dominant-held erasures, refugee-oriented ruptures, and juridical open-.” Schlund-Vials lays out, in no uncertain terms, the “problematic terrain” of justice in contemporary, post genocide Cambodia (and American geopolitics) through a provocative recapitulation of the political dynamics of the current Cambodian administration as well as the various US government administrations’ “politicized memory of a preventative humanitarianism” that “revises the script of the Vietnam War era to fit a humanitarian, not militaristic, end.”

The revelations in the first chapter, entitled “Atrocity Tourism” enlightens the reader to the “juridical mode of collected memory fixed to Vietnamese-oriented statecraft” in the critical analysis of the Tuol Sleng Prison and Choeung Ek Killing Fields which, in Schlund-Vials’ compassionate observation “fail to provide Cambodians with viable spaces for commemoration.” And more egregiously have become a “place where they use the bones of the dead to make business.” So begins Schlund-Vials’ quest for “contemplative commemoration: (through) Cambodian American memory work.”

The next chapter sets out on a crossing of sophisticated and politically revelatory chronicling of two American-produced cinematic portrayals: The Academy Award winning film The Killing Fields (Roland Joffe, director) and New Year Baby (Socheata Poeuv, author). Joffe’s film, and the back-story of the friendship between American journalist Sydney Schanberg and Dith Pran, former U.S. Army translator turned foreign press assistant is, on its surface, ”a story of two friends separated by (the realpolitik of) forces beyond their control”. But under Schlund –Vials’ tenacious scrutiny the “reframing” of failed U.S. policy in South East Asia, through this film, is transformed into an “exceptionalist narrative of reunion, salvation and redemption [through a] master narrative of cold war victimhood” that reconciles American military aggression through the trauma and redemption of the friendship, “forged in the interstices of war….literally screened, strategically staged and tactically projected by way of guilt, apology and reconciliation.”

Poeuv’s autobiographical film, based in the” Cambodian American present” is portrayed sympathetically as a “documentary-reliant on survivor memory instantiated by intergenerational inquiry (which) militates against familial silences and strives to connect survivors and their children by way of historical reclamation, collected family stories, and collective remembrance.” Schlund-Vials’ understandably impassioned assessment of New Year Baby is nonetheless accurate and deeply instructive. In fact, the contextual structure for evaluation of New Year Baby, a restructuring of an “unfinished memory work that grapples with intergenerational, familial silences and… partial knowledge of this past” serves as the template for exploration in the following chapters, that is, to “rationalize contemporary family frames” (through Cambodian American Memory Work) of the “1.5 generation” of Cambodian Americans.

The third chapter investigates “Cambodian American Life Writing” through the publications and reception politics of Loung Ung’s memoir: First They Killed My Father: A Daughter of Cambodia Remembers and Chanrithy Him’s memoir: When Broken Glass Floats: Growing Up under the Khmer Rouge. This moving chapter expresses the “anti-forgetting…labor of (Cambodian American) memory to expose catastrophic U.S. policy, lay bare international indifference, and underscore contemporary juridical inaction.” A clear rebuilding of identity of the Diaspora Cambodian American survivor evolves through this chapter which masticates the constructs and narratives of each work. The directive of Schlund-Vials in-depth considerations of Cambodian Life Writing, in this chapter is aimed at remembering the “politics of representing mass-scale loss… and the necessarily politicized act (of the memoir) that break(s) potent silences…in a largely un-reconciled milieu of competing national agendas (in the U.S and Cambodia).”

Chapter 4 crafts the fascinating trajectory of Cambodian American Hip Hop artist Prach Ly aka praCh’s up-bringing in “Cambodia Town” Long Beach California and the transnational strength of his lyrics and musical compositions. Schlund-Vials’ expression and analysis of praCh’s career and work “emblematically remembers a fractured genocidal history, a forgotten post conflict imaginary, and a ruptured Cambodian-American selfhood” and is decidedly upbeat. “Locating Who We Are and Where We Came From” develops thematically through clear and inspiring explorations of several albums; the lyrics and remix of traditional Cambodian musical instruments through original, contemporary compositions. Schlund-Vials predicates on praCh’s work which traces the “rapper’s evolving Cambodian American consciousness…and restive potential of Cambodian American selfhood.”

The epilogue chapter narrates the creative work of poet / performer/ visual artist Anida Yoeu Ali’s epic composition “Visiting Loss” which, in Gordon Fraser’s words: “employs a stream-of-consciousness narration evident in en-jambed lines, imagistic stanzas, and affective vignettes” and engages the central aims of Cambodian American memory work that “brings into dialogue genocide remembrance, collected memory and juridical activism.” Consecutively the installation “Palimpsest for Generation 1.5” activates the performance of Ali’s back as canvas upon which “intergenerational grievances are inscribed and summarily erased.” Through dress, gesture, and erased inscription, the performance artistry of Ali is an act of “re-memory” reminiscent of” nineteenth-century American slave narrative” that re-assembles a “communal memory without the luxury of justice at the level of the nation-state.” This potent closure to War, Genocide and Justice: Cambodian American Memory Work succinctly expresses the impactful narrative of this revelatory volume of the legacy of the Khmer Rouge era on today’s Cambodian Americans. Their contributions to contemporary society, on an international scale, and woven from the raw material of “memory work” have undoubtedly added vital contributions to the color, texture and weave of the fabric of remembrance in the face of annihilation.