The valley carved out by the Mbirurume River in the Western Province of the “Land of a Thousand Hills” was a scenic spot to get out of the car for a breeze and joke with the local kids.

Our driver, Didier, grumbled as we labored our way up to the knoll to where Nyange Church is located, the site of a uniquely grizzly massacre during the ’94 genocide. We took a jumpy turn onto a red dust road and arrived at the quiet, and closed, memorial site.

Through the gate the floor of the original church looked neatly re-cobbled after having been bulldozed into rubble with 2,000 refugee congregants inside, back in April of 1994.

The “cellar hatch” mass graves on the memorial site gave the eerie impression that the dead buried in these bunkers still have a lot on their minds and an open invitation to “c’mon down.”

This was our first visit to Nyange Church. But our driver knew that the stories, now muzzled, under these “cellar hatch” graves had much deeper reflections to illuminate the events in April of 1994. And on the road back from Kibuye, along the same highway, Didier drove us back up to Nyange Church, and this time was determined to find the self-appointed guide to enlighten us “dark tourists.”

On this Sunday morning the new church shelter, which is erected beside the memorial site, was vibrant with the rhythms of the morning prayer service and bustling with irreverent children who crowded around the car to see the “Mzungu” while Didier went looking for Aloys Rwamasirabo, the keeper of the memorial, to deliver us a guided tour of the site.

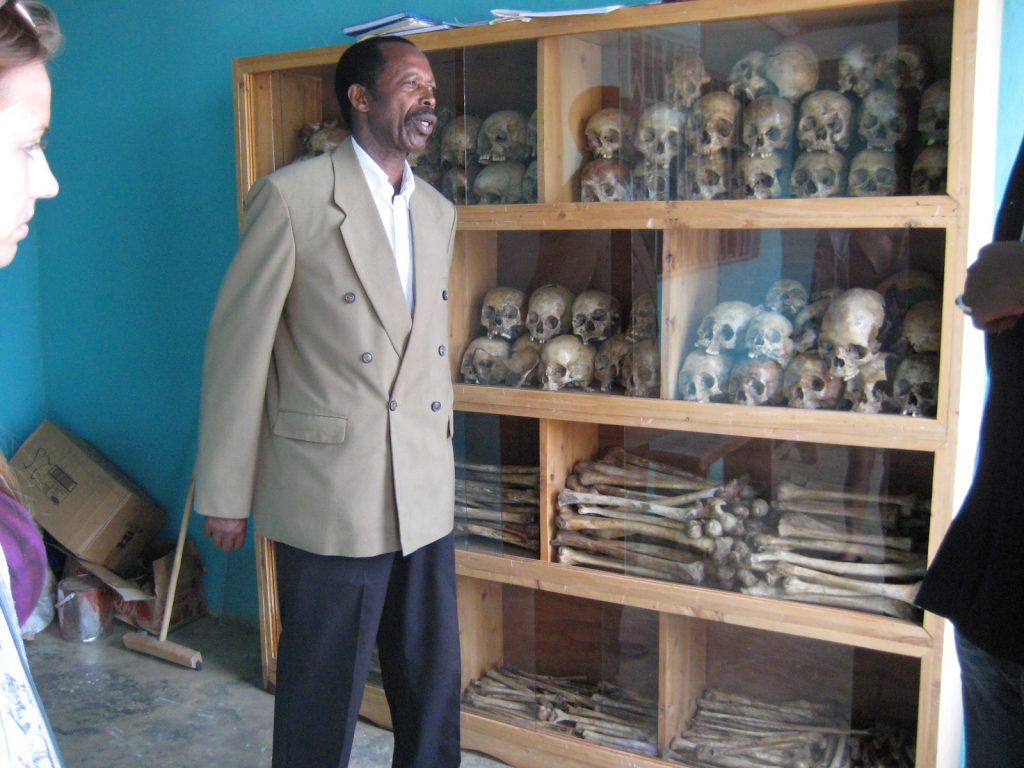

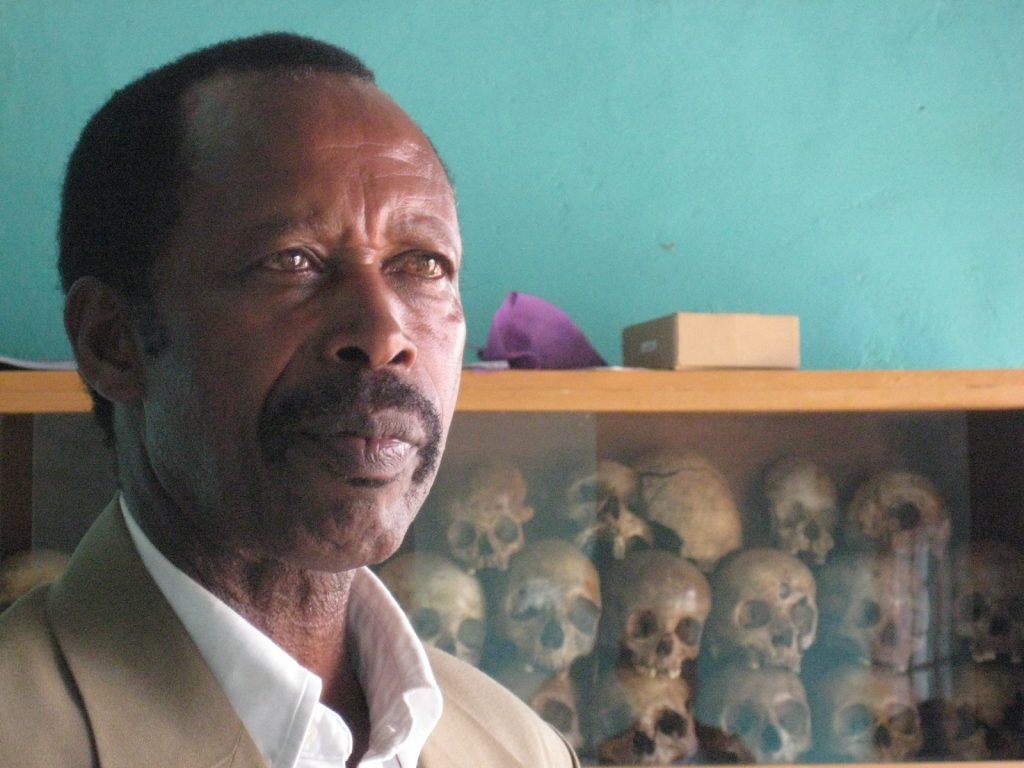

Aloys ushered us into the vestige of the Parish priests’ preparation room where the depth of the tale of Nyange Church was revealed to us among the carefully arranged bones of murdered congregants.

Aloys did not speak English, but our driver doubled as translator and we listened to the tale, first in Kinyarwanda, then in English. The rhythm of the story reverberated with the rhythm of the drums and song just outside the memorial gate. The effect was penetrating.’

I asked Aloys, through Didier, if he minded if I took his picture as his story unfolded.

My students grimaced at my bad taste. However Aloys did not seem perturbed by the infraction and proceeded to inform us of the gruesome chronology of the days in mid April, ‘94 when the church was encircled by the Interahamwe and other militia and the refugees inside were massacred and the building ultimately bulldozed into the ground with parishioners buried alive.

I asked Mr. Rwamasirabo about his personal story. He invited us into the tale of his family, and alluded to the terror of the community and those that were held hostage in the church. He told us that nine of his children, his mother and four sisters, who were all in the church for safety, had all perished during these terrible, no, cataclysmic hours. I asked if he would recite each name, so that I could record all the names of his family members who were murdered. Didier wrote down each name for me, and their proper spelling, in my journal. (I have the notebook with the names of all of Aloys’ family members open to the page of their recording by me now as I type.)

This naming; the sacred and time immemorial ritual to honor the dead was a moment of genuine sharing of grief and condolence for us all. I understood, if only marginally, the personal burden of suffering and loss that Aloys has carried these 20 years, now.

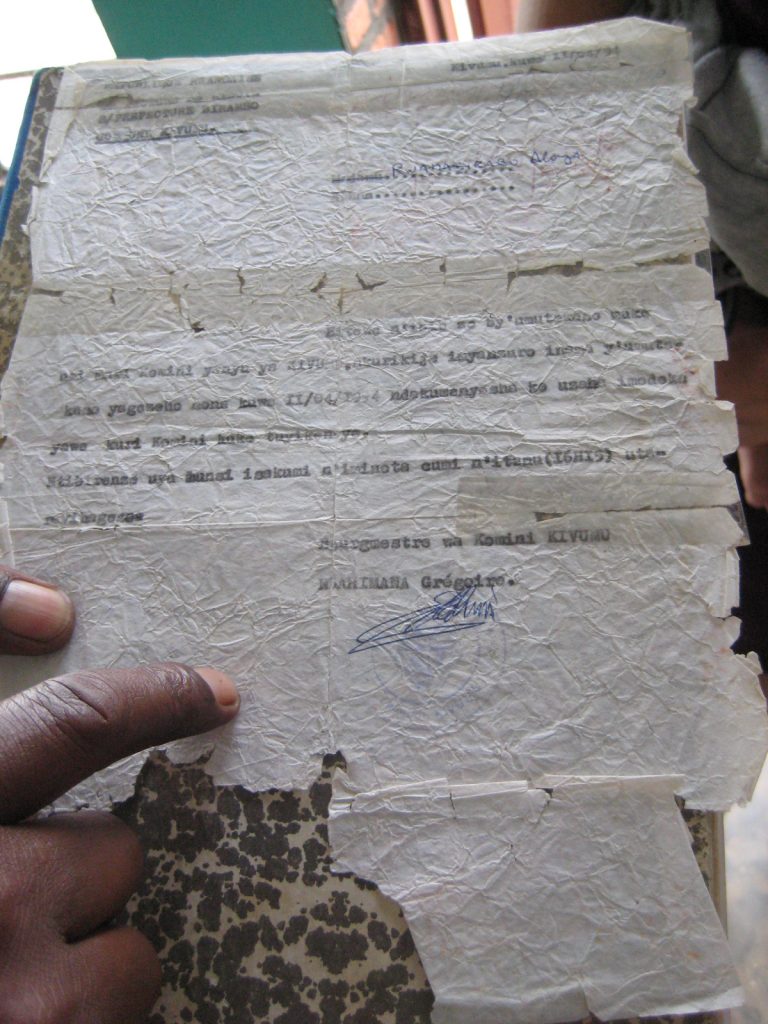

Other important details of Aloys’ narrative were translated for us. He was almost captured himself, when the district prefecture letter requested that he bring his car to the compound to be used for “official” purposes. He understood the deadly instructions of the letter for his life, and narrowly escaped plans for his murder.

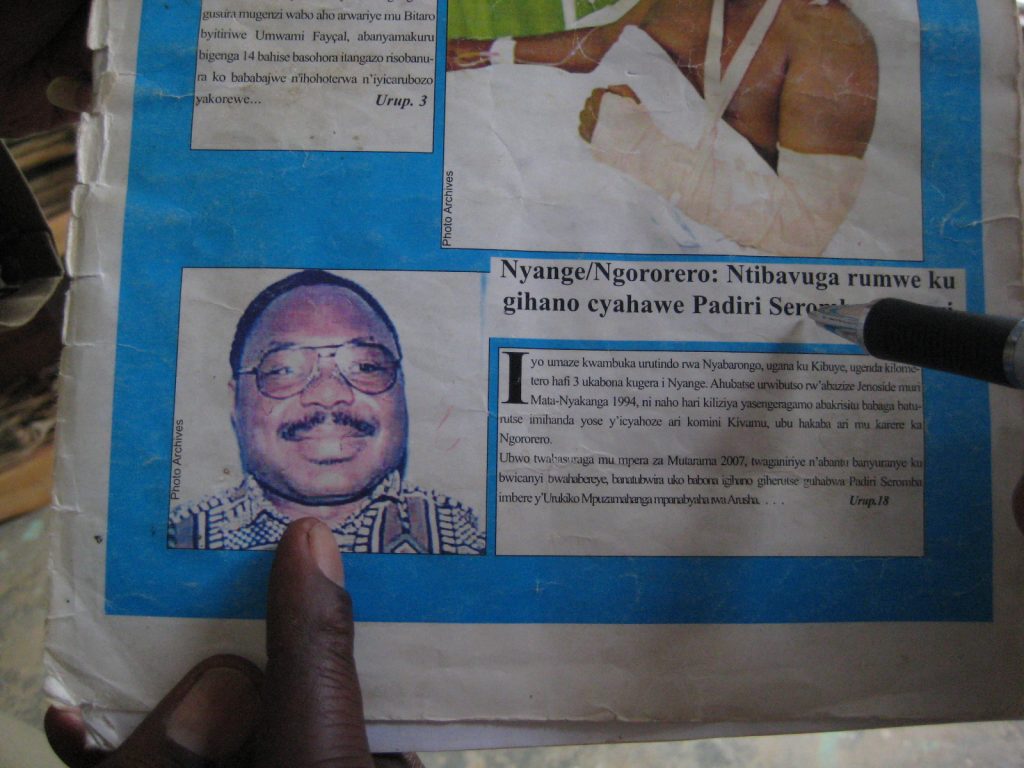

Through translator / guide Didier, Aloys also implicated the crimes of Nyange Church’s Priest Athanase Seromba, who was convicted of aiding and abetting genocide and crimes against humanity by the ICTR in 2002. Aloys informed us that he was singularly responsible for the ordering of the bulldozing of his church while his congregants hid inside. Seromba is serving a life sentence in Akpro-Missecrete prison in Benin.

Aloys concluded his story about the church today and the memorial site that he oversees. After the atrocities ended he tells us that the community was planning on building the new church right over the rubble of the massacre site. Aloys insisted that a holy church cannot be sanctified where the feet of the congregants tread on their murdered townsfolk. He initiated and oversaw the building and maintenance of this sacred memorial site and regularly guides visitors in and around the memorial.

Coreopsis and Chamomile grow around the memorial grounds today.

The fractured frame of a once radiant stained glass church window is propped against the remaining bricks of the destroyed church.

As we bundle back into Didier’s car he quietly mentions to me that he had never heard Aloys’ tell his personal story to the other visitors that he takes, regularly, to this site. I was humbled and very grateful to hear this intimate revelation.

And I share this deeper reflection of my heart, to you, across oceans, over time, transcending the miniscule prisons of our individual lives and down into those cellar hatch graves where this story is the point at the center of the universe, the place where the Tao reveals “heaven and earth meet” and our existence is one.

We climbed back into the sultry beauty of the West Province hills as the church service rang out in rhythm and sacred song.