The trajectories of epidemics / pandemics that spread throughout the centuries across the “New World” from the period of first contact until the present day have impacted indigenous communities drastically. Communicable vectors of smallpox, malaria, cholera, scarlet fever, typhoid, influenza, diphtheria, polio, measles, whooping cough, HIV aids and now Covid-19 have compromised, and in some cases succeeded in the elimination of entire populations during different historical periods, and in different regions around the hemisphere. In North America today, American Indian and Alaska Natives (AI/AN) are governmentaly self-organized as Tribal Nations with their sovereignty recognized by the U.S. Department of Justice as “domestic dependent nations.” (1.) The controversial Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968 established constitutional rights to AI/AN individuals. And, internationally, the 2007 UN Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples signifies a comprehensive framework for survival, dignity and well-being of indigenous people around the world; endorsed by the U.S. in 2010.

The triumphs of self-determination and sovereignty by our AI/AN relatives in relation to the United States was profoundly costly and spans its entire history from first contact until today. The synthesis of “pandemics” and “policy” that contributed to the current vulnerabilities and strengths of living AI/AN to respond to Covid-19 today has its roots in the dynamics of disease and conquests of colonial expansion and the rise of the nation-state.

Spaniards enslaving Native Americans, Universal History Archives Getty Images

Spaniards enslaving Native Americans, Universal History Archives Getty Images

The perspective that I have organized for this essay explores key sweeps of epidemics that broke out around north America along with critical policies that affected the lives of AI/AN peoples. How did self-determination and activism of indigenous Americans evolve in relation to epidemics pandemics? And, how can we understand the effects of these crises on the health and wellbeing of their communities today? What are key developments defining the impacts and connections between policy and pandemics over the historical periods from colonial expansion to nation to nation? How is the Tribal Nations government today responding to the Covid-19 crisis and what lessons from the past are influencing their responses today?

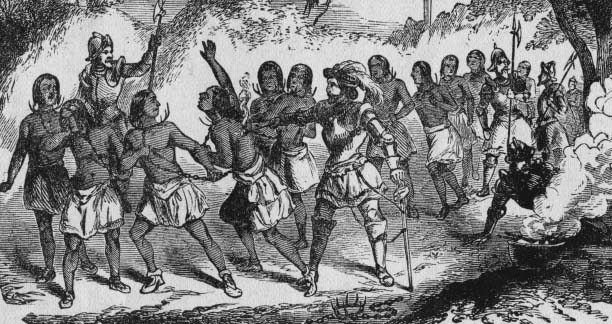

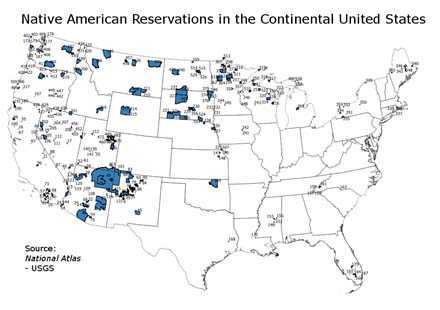

The most recently available statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau Public Information Office cite AI/AN population at approximately 2 percent of the total population, approximately 5.2 million individuals. (Including individuals in combination of one or more other races.) At the time of the census there were 325 federally recognized American Indian reservations and 566 federally recognized tribes. Income statistics conveyed the following: The median household income of single-race AI/AN was $36,252.00 as compared to $52,176.00 for the nation as-a-whole. The poverty rate was indicated at 29.2%, compared to the nation’s statistic of 15.9%. 26.9% of AI/AN lacked health insurance, whereas the national average was 14.5%. Only 13.5% of single-race AI/AN 25 or older held a bachelor’s degree or graduate / professional degree in 2014.

These figures expose some of the essential contemporary disparities in access to insured health care, education, employment and income that AI/AN face as structural underlying vulnerabilities to defend against a possible pandemic. These statistics also represent the unspoken culmination of 500 years of interactions between Tribal Nations, their governance and the periods of U.S. political history that set the preconditions for exceptional vulnerability to pandemics.

Access to clean and reliable running water and sanitation is another critical statistic that impacts current risk factors for AI/AN to Covid-19 exposure. According to a 2019 empirical study by the US Water Alliance National Action Plan, more than any other population group, AI/AN are more likely to face water access issues. 58 out of every 1000 AI/AN households lack complete plumbing. Reservations in particular are less likely to have clean and reliable water. Discriminatory policies in the development of access to water infrastructure by federal and state governments are perennial practices on Tribal lands which pose ongoing threats to these communities’ ability to foster good health and hygiene.

In 2009, the Rural and Remote Health Journal issued a letter to the editor which outlined the concerns of a potential pandemic and its containment within the social and cultural context of indigenous communities. The authors recognize that although many countries had created pandemic preparedness plans in response to the WHO Pandemic Preparedness directive, these plans neglected the needs of marginalized communities. Recognizing the historical toll that pandemics have had on indigenous communities, these populations the authors contend, have experienced extreme forms of disadvantage which are a result of pandemic prevention plans that have intentionally and or neglectfully marginalized indigenous populations. The authors note that exceptional risk factors still leave indigenous populations exceptionally vulnerable, today. Suspicion and fear of proposed measures to contain communicable diseases within the indigenous communities are a result of past policing control measures of isolation, incarceration and other punitive measures which exacerbated fear of retaliation, and which drove communities to cultural practices that could potentially amplify infection risk. Prevention strategies must involve, the authors recommend, full participation in decision making partnerships between indigenous peoples and government policy makers to incorporate an indigenous perspective / model of containment that would embrace genuine respect for indigenous communities and collaborative management of measures which foster community pandemic preparedness. The United Sates policy decisions have historically swept up AI/AN people and tribes along with larger American policy choices. (2.) The Indian “problem” of the Framers eventually became the Indian “wars” of the latter half of the 19th century. (3.) Today, the American “wars” on poverty, drugs and terror “continue to sweep up American Indians and Indian tribes into the morass of federal government policymaking…and have largely ignored and exploited the trust relationship with AI/AN to advance national goals.(4.) To these wars I add “the war” on Covid-19.

In February, 2020 The National Congress of American Indians issued an introductory report on Tribal Nations and The United States. This report covers a perspective that reflects upon concepts and practices of self-governance and the relationship between the Tribal Nations and the United States throughout history. The goals of this guide are to “ensure that policy decision makers at the local, state, and federal level understand their relationship to tribal governments as part of the American family of governments.” Since the 2010 U.S Census, the state of tribal federal recognition has increased as tribes seek and gain federal recognition. “Federally recognized” tribes are eligible for federal funding and are added to the Federal Register as their status is approved. As of February 2020 there are 574 tribal entities recognized and eligible for funding. These entities are now eligible for funding from the CARES Act.

The National Congress of American Indian recognizes 7 distinct periods of relations between AI/AN and “other American Governments” from 1492 to the present day.

1492 – 1828 (Colonial Period)

During this period, the interface between disease and colonial projects convened maliciously to conclude in almost complete annihilation of indigenous peoples living on the continent. This era was especially virulent in numbers of deaths of indigenous peoples, and these projects established a pattern of subjugation and dominance which exacerbated or originated epidemic diseases. The intentionally violent interventions of colonial enterprises unleashed “massively destructive forces on Native peoples and communities (including) enslavement, disease, loss of land and resources, forced removals and assaults on tribal religion, culture and language.” (5.) Variations of “configuration and impact” of the dual destructive forces of conquest and disease determined the “capacity of Native people and communities to directly resist, blunt or evade colonial invasions.” (6.) The early theory of “Virgin Soil Epidemics” explains indigenous deaths due to exposure to infection by European settlers to which they had no perceived immunity. Modern evaluation of this theory indicates that early disease rates were affected by nutrition, social structure, and other variables; that populations were not implicitly “virgin”, by virtue of the fact that some groups survived. (7.) The theory is important to understand to the degree that the effects of wars of conquest, enslavement, forced dispossession and removal, and destruction of material resources exacerbated the impact and virility of these diseases, and at various points in history and geographic region, in fact, impacted populations in a “later stage when processes of colonization were well underway.” (8.)

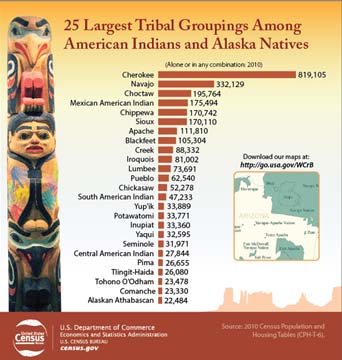

The timetable of policies and political practices that facilitated the annihilation of the pre-contact indigenous way of life during this era represents a continent worth of epidemics, massacres and indigenous resistance to consider. However, to consolidate the centuries and focus on the most impactful policies that dictated early depopulation and continue to fracture, marginalize, and compromise indigenous peoples we can examine the 1493 Papal Bull Doctrine of Discovery. The Doctrine of Discovery has set the trends in federal Indian law which has perennially undermined trust, plenary power and reserved rights of AI/AN. This 15th century legal precedent is the faulty foundation stone on the contemporary “ambiguous and uneven political framework for modern day Indigenous State relationships.” (9.)

Papal Bull “Inter Caetera” issued by Pope Alexander VI on May 4, 1493, Gilder Leherman Collection

The Doctrine of Discovery stated that any land inhabited by people who were not “Christian” can be considered “discovered” land and claimed by Christian rulers who have authority to overthrow “barbarous nations” and to forcibly bring Tribal Nations to “the faith” and /or enslavement. The decree’s impact formulated the legal context for dispossession of AI/AN lands and Cristian conversions.

The historic quantum leap in legal redress and authority for contemporary AI/AN issues of litigation was established with the 1941 Handbook of Federal Indian Law . However, this important legal precedent “characterized tribal authority as residual, rather than delegated.” (10.) And, historical reverberations of the Doctrine of Discovery on modern policy still impact contemporary indigenous sovereign territorial rights cases. 20th century judicial rulings involving the rights of compensation for removal of natural resources on tribal land and protection of native graves, for example, “become a way to show sympathy with Native peoples while at the same time denying them any substantive justice.” (11.) The long running myth of this doctrine relegates AI/AN people to the role of victim, “which drives behavior and determines policy with significant consequences. (12.)

Beginning in 1492, throughout first hundred years of colonial conquest estimated population decline of indigenous peoples was 70-90 percent. A combination of “smallpox, measles, influenza, bubonic plague, diphtheria, typhus, cholera, scarlet fever, whooping cough and malaria, combined with direct warfare, cultural disruption, economic chaos, reduced fertility and morbidity account for this depopulation (13.) Epidemics and demographic trends did not support evidence of continental pandemics. However, regional variations of infection were indicative of the “frequency of direct contact with Europeans, the nature of social systems, population density and distribution of intergroup relations, strength of cultural boundaries and general community health”. (14.) Compounded with the disastrous effects of epidemic diseases on the health of indigenous communities were factors of “excessive workload, reduced nutrition, warfare, soil depletion, poor sanitation and social disruption.” (15.) These factors predisposed indigenous populations to further constitutional health compromises such as decreased bone strength, dental decay, porotic hypertosis, decreased life expectancy, increased infant mortality, rickets, reduced immunity and other combinations of complex factors which undermined overall health. (16.) Today’s AI/AN peoples have experienced a remarkable population recovery. Although ongoing health, economic problems still plague indigenous Americans, progress in life expectancy and absolute population growth have indicated a full demographic recovery and possible surpassing since 1492. (17.)

Although the Colonial period is popularly recorded as having ended with the incorporation of the colonies into the United States of America in 1776, AI/AN recognize the end of this era with the election of Andrew Jackson in 1828, and the signing of the Indian Removal Act, in 1830.

1828 – 1887 (Removal, Reservation and Treaty Period) and 1887-1934 (Allotment; Assimilation Period)

This next 100+ years of AI/AN history enshrined into U.S. law the forced assimilation, territorial disenfranchisement, cultural and physical genocidal campaigns against American Indian (AI) peoples. The unrelenting demands for unimpeded access to land where AI populations resided includes countless federal laws and legislative acts that ended most AI/AN land tenure and fractured what remains, today. (18.) The Indian Removal Act represented key federal legislation that finally forced the expulsion of tens of thousands of eastern AI to federal territory west of the Mississippi River in exchange for unimpeded access to seized AI ancestral lands. Prior to this legislation, the largest populations of American Indian Nations: Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole attempted many conciliatory behaviors, policies, appeasements and conversions to assimilate in an attempt to coexist with settlers. Large scale farming, Western education and slave-holding practices are examples of shifts in ways of life AI/AN practiced in effort to preserve the right to self-determination. Legal redress and declaring war did little to impede settler squatting, speculation, and ultimately conquest of AI land and possessions east of the Mississippi. By 1837, the Jackson administration had removed 46,000 AI from ancestral lands east of the Mississippi. “opening 25 million acres of land to white settlement and to slavery”. (19.)

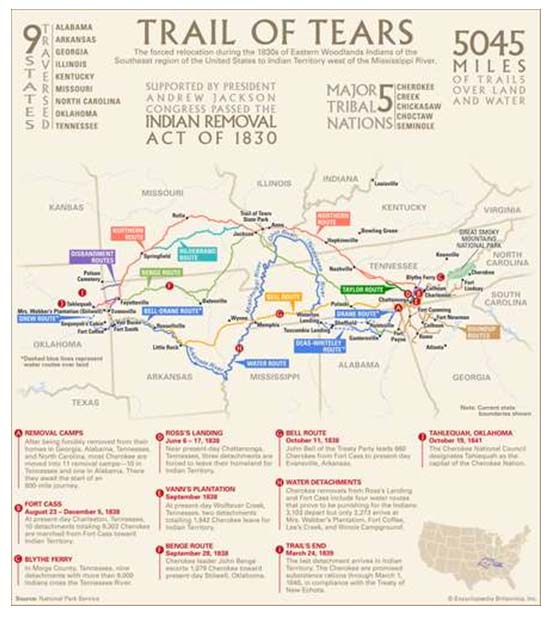

Trail of Tears, Routes, Statistics and Notable Events, Encyclopedia Britannica

The Trail of Tears is over 5000 miles long and covers nine states: Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma and Tennessee. (20.) The Trail of Tears is the iconic historical “forced march” event that crystalizes the cruelty, devastation and mass death due to disease, starvation and extreme weather conditions that these five tribes endured on their death march to what is today the state of Oklahoma former reservation areas.

Following its first appearance in New York in the spring of 1832, Vibrio Cholerae spread rapidly throughout the eastern United States. By fall, it had infected the routes over which southeastern tribes were being removed westward. (21.) “Vibrio Cholera takes hold primarily in unsanitary living conditions where people suffer from malnutrition and struggle daily with drastic environmental and economic changes. Contracting the disease usually requires ingestion of Vibrio Cholerae through contaminated water or food (transmitted through the excreta of infected carriers). Travelling through the digestive system to the intestines, the bacterium releases a toxin that drains fluids from the host’s system. The onset of the disease is sudden and explosive. Lacking premonitory symptoms, the victims experience severe vomiting and diarrhea, leading to prostration and rapid dehydration. Once the overburdened kidneys fail, toxic substances accumulate and, within a range of a few hours to several days, death occurs either from dehydration or internal-poisoning.“ (22.) Other diseases encountered along the trail ranged from pertussis, typhus, tuberculosis, mumps, smallpox, measles, influenza, and malaria. (23.)

Donald Vann, Cherokee artist: Men with Broken Hearts, 1994

In a paradoxical twist in politics and pandemics during this period in 1832 Congress enacted the Indian Vaccination Act; the first federal legislation to, ostensibly, protect the American Indian from epidemic outbreaks of smallpox as an act of good citizenship, and a form of state preventative medicine. Appropriations of approximately $17,000 were targeted to vaccinate AI residing on the edge of the frontier, along Mississippi River. Over 30, 000 individuals were inoculated by 1841. (24.) The link between public health, territorial expansion and state-building during this period reflects a confluence of conspiracy. The development of state funded preventative medicine for AI/AN people was conceived and implemented to facilitate Indian removal. The shocking wave of contagion during these episodic spreads of the disease made it clear to federal authorities that “epidemics were slowing the pace and inflating the costs of Congress’s newly formalized policy of Indian expropriation and removal.” (25.) The political lessons from this period emphasize the links between federal efforts to curb contagion in indigenous communities and the dynamics of land policy, land warrants, territorial bounties and homesteading laws to transfer wealth from property to constituents as entitlements, often with the aim of bolstering white migration and entrenching slavery. (26.)

The Dawes Act of 1887, had devastating consequences on AI/AN sovereignty, and continues to have consequences that compromise the health and wellbeing of AI/AN people today. The policy marked the end of the removal era and the beginning of the breakup of reservations by forming allotments to individuals within the reservation system. Indian lands that were sold or transferred to non-Indian parties but remain within reservation boundaries create a checkerboard pattern which impair the ability of AI/AN to use land to their own advantage for farming, ranching or other economic activities that require large contiguous sections of land. It also hampers access to lands that the tribe owns and uses in traditional ways. This checkerboarding also confuses access to governing authorities claims and creates mixed ownership confusion. Centuries of efforts to defend against ongoing “legalized” theft of resources and land, mismanagement, and unjust jurisdictional authority plague efforts toward sovereignty over reservation lands. Today, “tribal nations must continually inform and contest these decisions through education and lobbying in Congress and through grassroots activism and litigation.” (27.) Today, organizations such as National Congress of American Indians, National Indian Education Association, Native American Rights Fund, the Indian Law Resource Center and many others have forged an important bulwark against the historical tendencies of Congress to “use plenary power to damage or even destroy Indian nations.” (28.)

The pandemic of influenza 1918 – 1920 infected approximately 1.8 billion people and killed an estimated 50 million people across the world. Indigenous people suffered higher mortality rates than other populations. The exceptional vulnerability to the 1918 influenza by AI/AN was influenced by several factors, including “demographic characteristics, especially age and gender; socioeconomic status; availability of epidemic-appropriate resources; differential immunity related to health status and prior disease experience; variations in social distancing, from overcrowding through quarantines; and community organization and communication infrastructure.“ (29.)

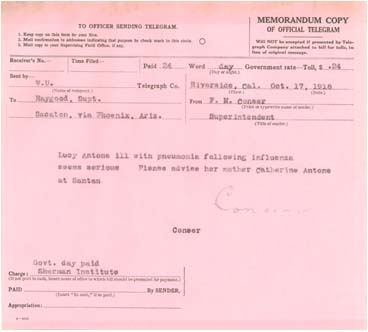

Telegram from an Indian Boarding School in Riverside, CA to the Pima Agency regarding the condition of student infected with influenza, asking that the child’s mother be notified (National Archives Administration at Riverside, CA)

The pandemic also changed the course of understanding global health and international response to epidemics. The 1918 flu pandemic claimed an estimated 50 million lives in three waves of infection. Some obvious parallels between the 1918 influenza and Covid-19 include the epidemiology of both diseases which affect the respiratory system; and that contagion is exacerbated by physical proximity, lack of access to hygiene and sanitation and health care facilities as well as the lethal combination of factors associated with poverty including malnutrition, immune deficiency and other poverty / stress exacerbated pre-existing health vulnerabilities. (30.) The first appropriations specifically earmarked for national health services to AI/AN was for $40,000.00 in 1911. The Snyder Act of 1921/23 provided the formal legislative authorization for health services. The exchange for services meant cession of tribal lands for the privilege of federal services including health services, the codification for these “provisions.” (31.)

1934 – Present

The National Congress of the American Indians (NCAI) divides this time period into several historical stages of development in their relationship with the U.S. government which reflects almost a century of impactful legislation on AI/AN nations.

Today, several federal agencies provide funding for AI/AN peoples, all of which are characterized by NCAI as chronically underfunded, marginalized, and entangled by 3rd party payer channels.

In 1954 the Surgeon General of the United States Public Health Service took over governance of AI/AN health affairs. A survey on “Health Services for American Indians” was conducted in 1957, known as “The Gold Book.” (32.) On July 1, 1955 the Indian Health Service (IHS) was established and worked under the Relocation/Employment Assistance Programs to facilitate relocation and assimilation of over 160,000 AI/AN from reservations to urban settings throughout the 1960’s. Although this program was deemed voluntary and incentivized, assimilation was structurally discriminatory and plagued with dim prospects for employment, discrimination and loss of cultural support.

By 1976 congressional concerns for the systemic marginalization of basic access to health services manifested in the 1976 Indian Health Care Improvement Act. (IHCIA) Funding for this service, from its inception until 1998 was reauthorized 4 times, with periods when funding was not agreed upon in congress, and the legislation was not passed. The IHCIA bill passed in 2009, during the 111th Congress, and included permanent reauthorization. It was signed into law by President Obama in March of 2010 as part of the Affordable Care Act. (33.) Today, formal consultation with tribal leaders on policy and program issues affecting the delivery of health services to AI/AN is facilitated through the National Indian Health Board. This 501c3 agency was established in 1985 to insure that treaty rights and laws are adhered to, and that benefits entitled to AI/AN people are complied with by the U.S. federal government and individual state and local agencies as they relate to all aspects of the health and common welfare of AI/AN as American citizens.

Covid-19

On April 10, 2020 the American Bar Association (ABA) convened a Covid-19 rapid response webinar on Issues Affecting Native American Communities during the Covid-19 Crisis. The webinar panelists included representatives from the ABA, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), the National Indian Health Board (NIHB), Lummi Indian Business Council, Chickasaw Nation Department of Health, CA Consortium for Urban Indian Health, Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Health Board, Committee on Natural Resources – Subcommittee for Indigenous Peoples of the United States, and the Bay Mills Indian Community of Michigan. The 2-hour webinar addressed presentations and discussions related to provisions in the Cares Act appropriations directed to Native communities; the specific health and operational challenges rural and urban Native communities face to protect against Covid-19; and the economic and legal impact that tribal communities face against the impact of the virus over the short term and long terms.

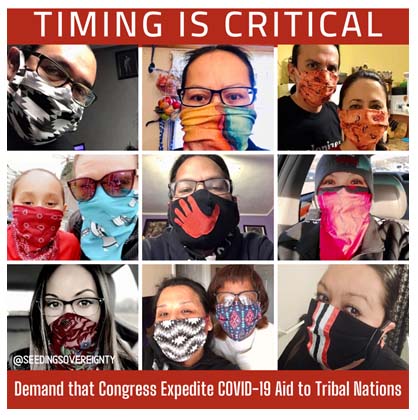

NCAI reported that inclusion of relief funds for AI/AN in CARES Act was not part of the first two phases of the plans’ packages, and that the parties convened are cognizant of the history of neglect implicit in the Federal government’s readiness to deliver aid to AI/AN communities. Informed by the absence of funding to AI/AN communities in the 2008 crisis to AI/AN community, robust requests for emergency response funds and oversight on expenditures were cited as priority concerns. NCAI recognized the penchant for AI/AN communities as being seen as “collateral damage” in past pandemics is a current risk. Collectivized mitigation by AI/AN leaders is going to be essential as the population is already at higher risk than other communities. The 3rd phase of the CARES act signed into law H.R. 748 on March 27, 2020 included comprehensive appropriations for AI/AN communities and individuals. NCAI acted as a “clearinghouse” for the organization and orchestration of priorities which were brought to Congress. This third phase of appropriations included funds to help Native communities respond to the pandemic. Policy priorities were determined by tribal leaders across the country and divided into policy priority working groups for healthcare, nutrition, education, housing and governance. NCAI Covid-19 Resources for Indian Country website conveys important legislative updates, White House communications, and key administrative decisions on pandemic response initiatives. General Covid-19 information pages include links to domestic and international medical experts to answer top “corona questions”. FAQ links for individuals are regularly updated as the progression of the disease unfolds. (34.)

NIHB’s presentation expressed concerns about funding flexibility with respect for tribal governments ability to direct funds for their specific community’s needs. NIHB appropriations are complicated with much of the funding coming from 3rd party billing. This complication could potentially hinder any emergency rapid response funding. NIBH also established a Covid-19 Tribal Resource Center’s website dedicated to making sure that tribes are informed and regularly updated on resources and assistance to help respond to the pandemic. Links to webinars and teleconferences, communication, health tools and advocacy tools as well as tribal pandemic response plans are available on this comprehensive site. (35.)

Tribal Elders from various regions spoke about concerns for adequate, preemptive preparedness planning to mitigate exposure. They also discussed the lack of a genuine relationship of trust between the IHS and Tribal communities with a decades old pattern of diminishing services and neglect. It was reported that testing and tracing has been initiated, but that they are insufficient, and that CDC or NIH models for procedure may not serve the needs of the community appropriately. A lack of PPE is endemic, and some tribal colleges are manufacturing 3D printed equipment. The closure of casinos presents issues for health insurance and municipal revenue. Casinos are the municipal revenue stream for reservations, and the health care stream for employees. Tribal casinos are not eligible for SBA loans and there has been no response to emails or phone calls to SBA officials. Some reservation areas do not have alternate care sites available for covid-19 patients and no uniform liability protections during declared emergencies. (36.)

Many current news sources have covered developments in the rapid spread of Covid-19 among the AI/AN population. Overwhelmingly and repeatedly, alarming concerns about the vulnerabilities due to pre-existing conditions that burden the AI/AN communities (diabetes, heart disease, respiratory illnesses, impaired immunity among other diseases) make the headlines. Extenuating socio/economic conditions are also covered: extended family situations under close quarters; lack of access to clean running water; nutritional and communications access, are all alarming leading news. These re-occurring patterns of population wide vulnerability to pandemics due to class domination are as old as the histories reflected in this essay and in the statistics of Covid-19 cases and deaths among AI/AN.

This perspective on pandemics, policy and indigenous Americans, past and present touches upon the evolution and struggles for self-determination and outright survival that AI/AN people have faced in their 500 year relationship with governing forces of the dominating culture from the era of first contact to Covid-19. Policies that facilitated colonial conquest and the nation state and the response to pandemic infections in AI/AN communities have overwhelmingly facilitated expropriation. The pattern that emerges and continues to define the relationship of Tribal Nations to the Federal government is the overarching entitlement to AI/AN territory, the paternalistic cultural domination over Tribal ways of life, and the tendency to treat AI/AN peoples as “collateral damage” in emergency responses. Nevertheless, this essay reveals the resiliency and self-governing strategies of the AI/AN which has emerged into a formidable advocacy collective defending the health and wellbeing of the Indian Nations today.

It was not until 1924 that full citizenship was granted to AI/AN individuals. (37.) Full states’ rights to vote did not occur until 1948. (38.) Yet, this FY 2020 NCAI Indian Country Budget request for key areas of federal appropriations makes a robust call to address structural inequalities in infrastructure, roads, housing, water and sewer systems, broadband, public safety and education, as well as climate change. For those of living our daily lives outside of intimacy with tribal communities, deepening our understanding of the relationship between pandemics and policies that have affected our indigenous neighbors is a universal civic responsibility. Recognizing the potential for our representatives to see Covid-19 as a convenient form of population control makes it critical that citizens understand and address the structural inequalities that our neighbors have endured, and advocate in concert so that their survival probabilities improve against Covid-19, and that they can thrive with sovereignty, dignity and in full health.

Sources Cited:

- S Department of Justice Archives

- Fletcher, Matthew and Peter Vicaire Indian Wars: Old and New Michigan State College of Law Indigenous Law and Policy Center, Working Paper Series May, 2011 (pg. 3)

- (pg.3)

- Ibid 2. (pg.3)

- Olster, Jeffrey Genocide and American Indian History: Early National History, Native American History, March 2015 (pg.1)

- Ibid (pg. 1)

- Ubelaker, Douglas Patterns of Demographic Change in the Americas: Human Biology, Vol 64 No. 3 Special Issue on the Biological Anthropology of New World Populations, June 1992 (pg. 372)

- 5 (pg. 2)

- Wilkins, David Deconstructing the Doctrine of Discovery: Indian Country Today, Oct. 2014

- Barsh, Russel Lawrence Felix S. Cohens Handbook of Federal Indian Law, 1982 ed. Washington Law Review, Volume 57, No. 4, November 1982 (pg. 801)

- 9.

- 9.

- 7 (pg. 364)

- 7. (pg. 364)

- 7. (pg. 367)

- 7. (pgs. 368-381)

- 7. (pg. 372)

- Indian Land Tenure Foundation

- PBS Indian Removal

- National Park Service: Trail of Tears National Historic Trail

- Powers, Ramon and James Leiker Cholera Among the Plains Indians: Perceptions, Causes, Consequences: Western Historical Quarterly Vol. 29, No. 3 August 1988 (pg. 320)

- 20. (pg. 327)

- Union to Disunion: Life on the Trail

- Rubin, Ruth State Preventative Medicine: Public Health, Indian Removal, and the Growth of State Capacity, 1800-1850, University of Chicago, working draft (pg. 1)

- 24. (pg. 4)

- Ibid, 24. (pg. 9)

- 18

- 18.

- Brady, Benjamin and Howard Bahr The Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1920 among the Navajos: Marginality, Mortality and the Implications of Some Neglected Eyewitness Accounts: American Indian Quarterly, Vol 38, No 4, Fall 2014

- Spinney, Laura Time Magazine: March, 2020

- Press, Daniel A Study of Indian Health Service and Indian Tribal Involvement in Health) Dept of Health, Education and Welfare, 1974 (pg. 17)

- Gold Book, The First 50 Years of the Indian Health Service

- Tribal Health Reform Resource Center

- Issues Affecting Native American Communities during the Covid-19 Crisis

- 33.

- 33.

- National Constitution Center

- 37.